Added on 24 March 2017

By WpFlara!-14?!

0 Comments

Innovating is hard. There is not a clear road, and a disorienting number of possible directions to follow. Innovating and succeeding in the market is even harder; but there are a few lessons we can learn from innovating products that have succeeded in the past. Amy Jo Kim has put together a Game Thinking Toolkit, a powerful system that integrates many processes and practices she learned as part of the design team at games like Rock Band and The Sims. It turns out that a lot of the principles that game designers have used for creating successful innovative games can help us innovate successfully in all sorts of fields.

Lesson 1. Assume You Will Be Wrong

There is a lot in common between good game design practices and other product discovery methodologies like lean startup, UX centered design, and design thinking. One of the things all these methodologies agree is about the chances of succeeding at our first attempt at product development: every time we are coming up with new products or solutions to problems we make a lot of assumptions -many of them unconsciously- and a lot of these assumptions turn out to be wrong.

To counter this problem all modern product discovery methodologies prescribe as a solution user-centered iterative development: focus on understanding your user needs first, and then develop solutions in an iterative way where user testing and course correction is part of the development process throughout. If you know that most likely you will be wrong, early and continuous testing will let you correct before is too late or too expensive. “You can use an eraser on the drafting table or a sledge hammer on the construction site” says the famous Frank Lloyd Wright’s quote.

When you assume that you will be wrong, plan for it, and do your best to uncover the wrongs as early as possible, the whole process will be more effective and smoother.

Lesson 2. Develop a Core Learning Loop First

If the first lesson is common to many other methodologies, this one is more unique to game thinking. The concept of a core loop is something common in games but game thinking expands its application to all sorts of products and experiences.

All games have a core set of activities that the player repeats over and over to advance through the game. In a casual game like Bejeweled the core loop is pretty simple: you solve match-3 puzzles, which let you level up and earn new powers, which make it more fun to solve more match-3 puzzles, level up more, earn more… and so on. These core repeatable activities are called core loops and are the foundation to long-term engagement. In essence, players complete rewarding activities that compel them to come back and do more rewarding activities. Social networks are an easy example of products that are not games that have a core loop. In Twitter and Facebook for example, the loop would be about reading and responding to updates and messages, as you engage with people and topics that you find interesting, your updates will be tailored around them, making your updates more interesting and engaging for you, which will lead you to interact more, and so on.

The other aspect that is unique in Amy Jo Kim’s toolkit is that we are not just talking about core-loops but about core-learning-loops: loops where the repeating activities allow the player or user to learn or get better at something. “Fun is just another word for learning” is a well known quote from Raph Koster, author of A Theory of Fun for Game Design. It is true; the most engaging games include a mastery component. If you add this element of mastery and transformation to your loop it will be much more powerful.

Why developing this core-learning-loop first? Because in most cases if you cannot figure out how to keep people around your product or experience, nothing else matters. You can spend as much as you want on marketing, but if the people you bring from your marketing efforts don’t stay, become fans, and recommend your game or experience to others, you won’t succeed. In other words you will have a leaky bucket that can never be filled, no matter how much water you manage to put in.

Developing a loop that keeps players around is much easier if you have found something that connects emotionally with your users or players. In the case of a utilitarian product this would be the value proposition, you offer the solution to a problem that your users have, and that is enough of a reason for them to be invested. So although the first part of the product that you should develop is this core-loop, you need to be clear about your value proposition and how it connects to your users.

In the case of an entertainment product, finding that emotional connection is much trickier. The value proposition, providing an entertaining game, is not enough in a market filled with games claiming to be entertaining. In the case of games and other purely entertainment products, figuring out how to connect emotionally through the right theme or IP might actually make it easier to find the right loop. In the case of games and other interactive experiences engagement will also be stronger if you tie your loop to other ingredients that contribute to engagement like stories. You can read more about how concept art can help you test and validate you emotional connection in another article here. You can also find out more about how core-loops can connect to other ingredients in your game to strengthen engagement in this article here.

Lesson 3. Test First with Your Super-Fans, Not Your Core Market

This is another thing that is unique to Amy Jo Kim’s game thinking approach. At the beginning of the process, the people that you are going to learn the most are not the people that will be your core market, but the people that are already very invested: your early adopters or super-fans. This recommendation is very different to what you hear from other methodologies. The most common recommendation is that you need to test your ideas and prototypes with your target market, with the people that will eventually be your core customers. That makes sense, a successful game or product needs to attract a wider audience, and not just the super committed fans willing to adopt any new product in the niche they love.

However, when you are truly innovating your product will be difficult to grasp for most people. People in your target market will get it once you have polished all the rough edges and figure out a smooth user experience, but that comes at the final stages. At the beginning you will have a lot of rough edges and you should not be spending time smoothing them out, but figuring out if the core features are the right ones. The most qualified people to give you feedback about those core features, the ones that will be able to see beyond the rough edges, are your early adopters and visionaries, not your core market. This approach, although counter intuitive at first, is what allowed ground breaking games like Rock Band and the Sims come to fruition and become the huge market success they are. Of course you want to make sure that your value proposition, or your theme and IP in the case of a game purely for entertainment, will connect to your larger target market, but to figure out the right core features, test with your super-fans.

Conclusion

Innovating successfully is hard, but following some lessons from previous innovative and successful products will increase our chances. The Game Thinking toolkit that Amy Jo Kim has put together is a very useful roadmap to navigate the confusing waters of innovative product development.

If you want to learn more in depth about this system and save time in your product development, check out Game Thinking Live, a yearly conference and workshop happening at the end of March in San Francisco. I will be participating as a coach and if you are interested in attending you can get a 30% discount by using the code FELIPE30.

The Bohemian Rhapsody Experience is a virtual reality music video for Google Cardboard based on Queen’s classic song; produced by Enosis VR in collaboration with Google and Queen, and released last September with some great reviews. David Deal from SuperHype blog called the experience “a more compelling glimpse of the future of VR than any demos and new products coming out of Silicon Valley recently,” and used the piece as a prime example of the kind of content that will make VR great.

I worked with Enosis VR as Art Director to help bring their prototype to a high quality polished experience. Working in this project was in itself a great experience that taught quite a few things about VR and helped me clarify some personal ideas about what makes VR compelling and what ingredients can help us make more powerful virtual reality content. In this article I will group some of these ideas into 3 lessons.

Lesson 1: VR Is About Providing Experiences

At its core, engaging VR is not about storytelling, it is not about interactivity, and it is not about agency. There is a lot of talk in the industry about VR being a storytelling medium on one hand, and about being an interactive medium that can give us a unique sense of agency on the other. I’ve seen compelling examples in VR of both storytelling and interactivity, but one thing that becomes clear to me after working in Bohemian Rhapsody is that at its core VR is not about telling stories or about providing agency but about providing experiences.

If you think of some of the most memorable experiences in your own life -from being present at the birth of your child, to witnessing a natural disaster – you know that powerful experiences do not necessarily depend on having agency or being told a story.

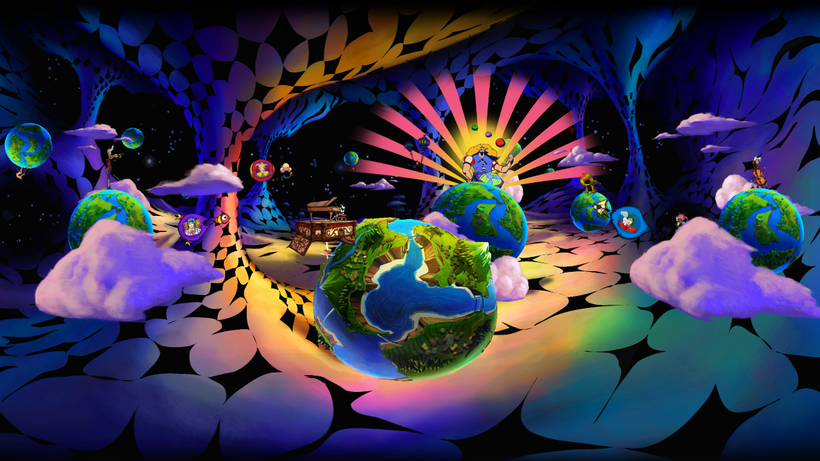

Bohemian Rhapsody has some pieces of stories and a little bit of agency -as your gaze triggers specific animations and events- but its power lies in letting you experience a powerful piece of music in a new way, in letting you experience a series of fantastic environments that enhance your connection to a powerful song.

I am not saying that there is no room in VR for storytelling, interactivity, and agency. They all can be important tools to help us provide powerful experiences, but none of them is essential. There are in fact many different kinds of experiences that can be powerful, some because of the sense of agency they provide, like Tilt Brush, and some despite having very limited agency, like the VR documentary 6×9. The same goes with storytelling. Stories are part of the way we understand the world around us, but that doesn’t mean that all the experiences that have impacted us came with a story behind them. Have you witnessed a big accident? We create stories about powerful experiences like these to remember and assimilate them; the story comes after, not before.

Storytelling, interactivity, and agency are all tools that help us create better experiences, but none of them is indispensable.

Lesson 2: Emotional connection is key to make the experience powerful

Powerful experiences connect with our emotions, they arise our feelings. An experience that doesn’t trigger any emotions is a dull experience, neither memorable nor engaging. It doesn’t need to be any specific emotion. It could be a sense of creativity and power like in Tilt Brush; it could be a sense of empathy like in the winning documentary “Notes on Blindness: Into Darkness”; or a meditative sense of awe like in Shape Space VR “Zen Parade.” What matters when you are creating a powerful experience is that all the elements in the experience work together to reinforce the emotions you are after.

In developing Bohemian Rhapsody we were lucky to have as a starting point a masterpiece of classical rock that already connects emotionally to many people. Our challenge was to create environments, characters, and animations that broadened and reinforced the emotions already present in the music.

In another article, “The 5 Ingredients of Successful Games and VR Experiences” I talked about Themes, and how Themes when done well can help to tie all the elements of your experience and make it easier to connect emotionally with your player. In the case of Bohemian Rhapsody, the song acted as our unifying Theme, and as any great Theme it included already an attitude and a point of view about the world that made it easier to come up with all the other pieces of the puzzle.

You don’t need to base your experience on a powerful song, but I believe it is essential to find a Theme with a specific point of view to tie your experience together and connect with your audience emotionally.

Lesson 3: Powerful experiences don’t need to be realistic but need to be coherent

The ability of VR to give us a sense of presence -that gut feeling of really being in front of what we are seeing- is what makes us talk about VR content in terms of experiences. But that sense of presence is not the same in all VR pieces.

Richard Skarbez, a PhD candidate at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, has found in a series of studies that Presence in VR is created by two key components: immersion and coherence. Immersion refers to the feeling of being in another place, and it comes with the medium. When you look through your VR viewer you already feel like you are inside an environment. Coherence however, is what makes us feel that the place we are surrounded by is real. According to Skarbez’ studies, both components are essential to create a sense of presence. If either on them is missing, the illusion brakes.

The interesting thing is that the sense of presence does not depend on the environment matching reality. In fact, when the environment is realistic our expectations are much higher. There are a lot of subtleties about how reality works -lighting, materials, natural motion, natural behavior- that we expect when looking at a realistic environment, and if something is not working as we know it should, the coherence and the sense of presence breaks (you can listen to a great interview of Richard Skarbez and his findings in this interview by Kent Bye from the Voices of VR podcast).

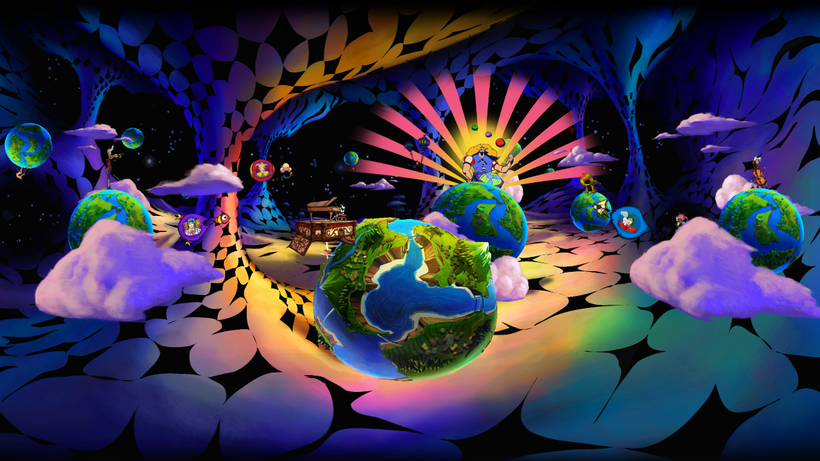

When developing Bohemian Rhapsody we confirmed that highly stylized content did not break the sense of presence. Even when we mixed 2D and 3D characters and environments, we found that as long as the assets came together in a coherent manner we still could achieve a sense of presence. To unify 2D and 3D assets we used mostly two things: a unified perspective and consistent flat lighting. Whenever we introduced other kinds of lighting, or the perspective painted in the 2D assets was different from the 3D camera perspective, the illusion of a coherent world and the sense of presence broke.

Also, although your experience needs to be consistent, consistency can be fluid. The Bohemian Rhapsody Experience contains different scenes with radically different styles as you can see in the illustrations shown in this article. However, each scene was internally coherent, and each scene was consistent with the song, the primary unifying Theme. Since Bohemian Rhapsody contains different music styles, the different visual styles didn’t clash but supported the complexity of the song. I believe the same could work with other strong Themes. As long as each scene is internally consistent and consistent with a unifying Theme, you can have different treatments within the same piece without breaking the unity of the experience as a whole. To further strengthen the connection between scenes we created an overall narrative of Freddy Mercury’s journey to self-realization. This narrative, although not always obvious, worked as a secondary Theme that allowed us to establish connections between the different parts of the experience.

Conclusion

At its core, engaging VR is not about storytelling, it is not about interactivity, and it is not about agency. It is about engaging experiences. Although storytelling, interactivity, and agency can all help us create powerful experiences, they are just tools. None of them is indispensable to make engaging VR content. Many powerful experiences in our lives involve very little agency and story. All however connect to our emotions and feel real. Whatever tools we decide to use, storytelling, interactivity, or agency, we need to make sure that we connect emotionally to our users, and we need to make sure the sense of presence is preserved by making the experience as a whole coherent.