Added on 14 July 2017

By WpFlara!-14?!

0 Comments

I get tired of the games vs. story argument. Not to mention the entertainment vs. practical utility argument. In many cases these discussions come from assumptions that are wrong, and the problem is that if you get caught up in them, they can limit your options to making great experiences. Even some very smart experts have contributed to the confusion. “Video Games Are Better Without Stories” says Ian Blogost in a recent article in the Atlantic. While Robert Marks tells us that “Video Games Aren’t Just Better With Stories, They Are Stories” in another recent article at CG Magazine. I would say yes, video games are sometimes better without stories, and yes, some video games are stories. Neither statement is always true or false. I think the discussion gets muddled from two erroneous assumptions: first, that games are a medium, and two, that storytelling is the primary goal of a medium.

Let me elaborate. Games are not a medium, just the same way stories are not a medium; they are both the product of our need to understand and assimilate our experience of reality. Neither of them is a medium, but you can make both stories and games using almost any medium. The written word is a medium, painting is a medium, film is a medium. I’d like to avoid getting into philosophical definitions of what is a medium here but think of writing: the written word is a medium, a means to communicate stuff. As any other medium it can be used in different ways: to tell stories, to create games, or to solve other practical problems that have little to do with either of them. You can use the written word to make games like you do in cross-puzzles, tell stories like you do in a novel, or solve a practical problem like we do when we write a list to remember what to buy at the supermarket. You can do the same with other media: you can use still pictures to create hidden object games like in “I Spy” books, tell stories like in a movie poster, or solve a practical problem like when you get a photo ID to prove your identity.

So what are games and stories exactly? Why have they been an important part of every culture around the world? If you think about it they are both tools that help us get better at living and dealing with the reality around us. In real life we like to accomplish things, and games let us practice coming up with good strategies to accomplish goals. In real life we also need to make sense of what happens to us, and stories help us do that. Both games and stories help us get better at living and understanding our lives.

Games are formal systems with clearly defined goals and rules. In a way they are a simplification of reality. In real life we have goals that we want to achieve, and to do that we need figure out what are the best strategies to achieve them. Figuring out the right strategies includes finding out what are the best paths to achieve our goals, what resources do we need, how to get those resources, and how to best manage them. In most cases, there are also general rules we can follow to increase our chance of reaching our objectives: if you complete your assignments you have a higher chance to pass your class, if you have experience working at a game company you have a higher chance to get hired at another game company. Games are similar to life but simpler. While in games all the goals and rules are very clear, reality is a lot fuzzier: goals vary from situation to situation, and rules are in most cases only guidelines that don’t assure anything and tend to change over time. In a way, games let us take a stab at aspects of life in simpler and safer settings. They let us experience aspects of reality, and they give us the opportunity to explore and figure out the best ways to reach goals. Games are great because they give us agency and let us practice how to better use it to accomplish specific things.

Stories are also simplifications, but they focus in structuring our experience of reality to provide meaning. They don’t focus on letting us try different ways of achieving a goal, but rather on helping us understand our experiences and make them meaningful. When we tell a story we organize our actions and the events around us in ways that make it all more intelligible, in ways that make sense. In a traditional story there is always some sort of conflict that gets resolved somehow at the end: There is a beginning, where a protagonist wants something but finds one or more antagonists or obstacles that don’t let him get it; there is a middle, where the protagonist tries different ways to overcome the obstacles and reach his/her goals; and there is an end or resolution where he/she succeeds or fails in achieving his /her goals. Stories help us understand life experiences better in terms of conflict and resolution. Stories are compelling not because they let us take a stab at dealing with reality, but because they let us make sense of it. The core value of a story is in creating meaning out of otherwise chaotic random events.

If we wanted to talk about games as a medium I would say that rather than videogames being a medium, computer applications are the medium, and you can use computer applications to make games, tell stories, or solve problems. Or a combination of all three. Most modern videogames contain both game systems, and elements of storytelling. Other applications like CodeSpark Academy -a game for mobile devices with a lot of storytelling elements that aims at teaching kids the principles of computer science in a fun way- even include elements of all three: games, storytelling, and solving a real need.

I think it is much more useful to think of applications for different media in terms of experiences, not games or stories.

Think of real life experiences. Some experiences are great because of agency, because we did it. Do you remember the first time you rode your bike without training wheels, or the first time you climbed a very tall mountain? What makes these experiences great is that we did them ourselves. Many people had done the same thing before, but they are still great because this time we were the ones who did them.

Other experiences are great because of the story or meaning behind it, like when the first person in your family graduates from college. That can be a great experience because of what it means for you and your family, even if you were not the one who did it.

Other experiences are great because they solve a practical problem, like finding a good car mechanic that fixes your car at a reasonable price.

But agency, meaning, and practical utility are not mutually exclusive. The experience of climbing a tall mountain would be even more memorable if there is more meaning or a story behind it, like if you suffered from a physical ailment since you were a kid and were nonetheless able to overcome it and climb after years of preparation and struggle. Fixing your car (practical utility) would be more memorable if you are the one who did it (agency), and even more if the car was your grandfather’s car that is full or childhood memories (meaning).

The same goes with computer applications, from videogames to VR and AR applications. Being able to use your agency to overcome interesting challenges does not exclude the possibility of making those challenges more meaningful, or useful. Mixing game and story to add both meaning and agency can make the experience much more memorable. Just as adding practical utility could.

Games, stories, and practical utility are not exclusive. It is not easy to combine these three aspects in a compelling meaningful way -just as in real life experiences- but following the right process makes it much easier. When you set the right clear goals, use the right ingredients, and use an iterative process with the right prototypes, making rich powerful experiences becomes easier. You can see more information on how to do that in the articles from this same site that I just linked to in the previous paragraph.

I would love to hear your thoughts and comments about the intersection of game mechanics, storytelling, and utility.

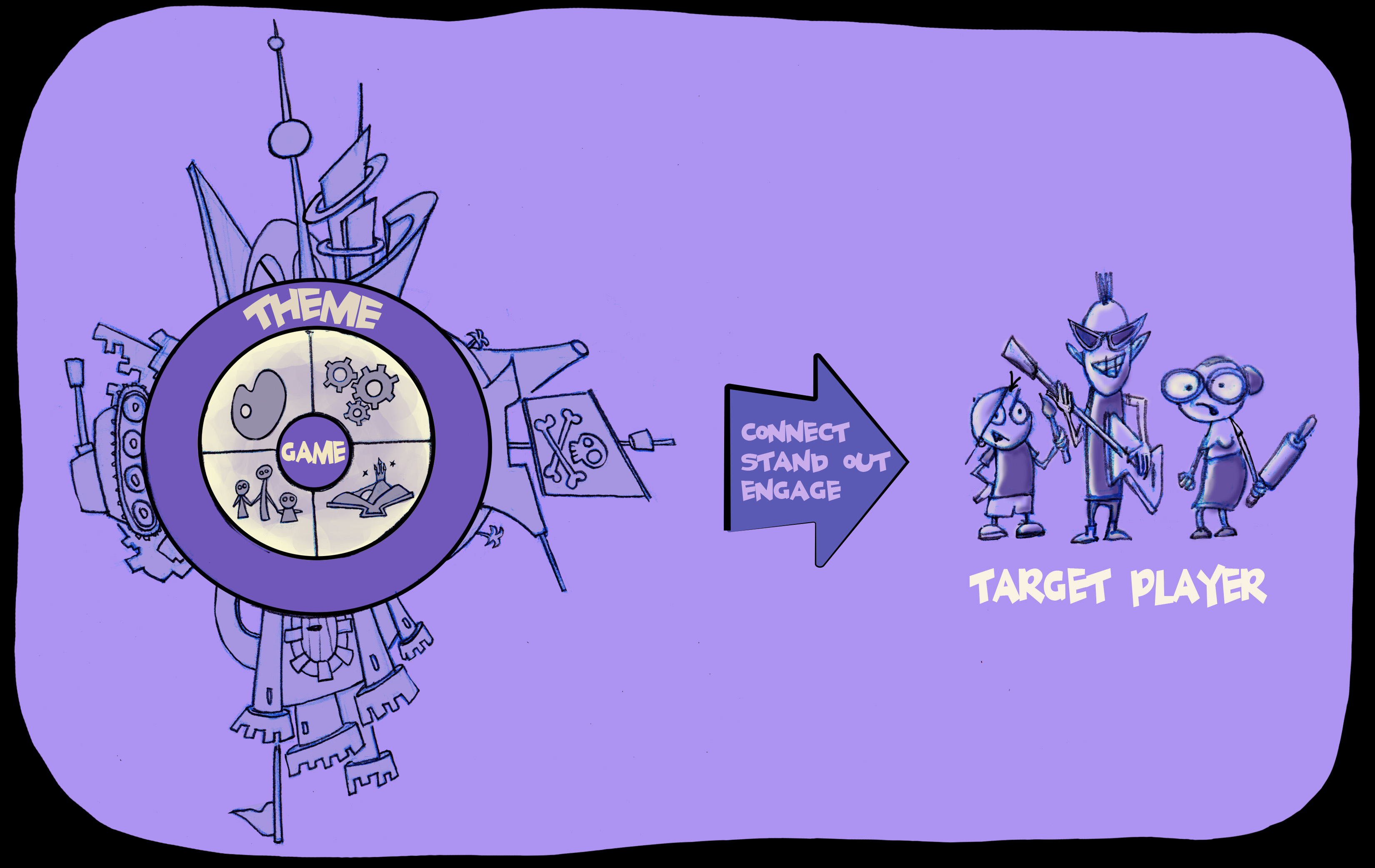

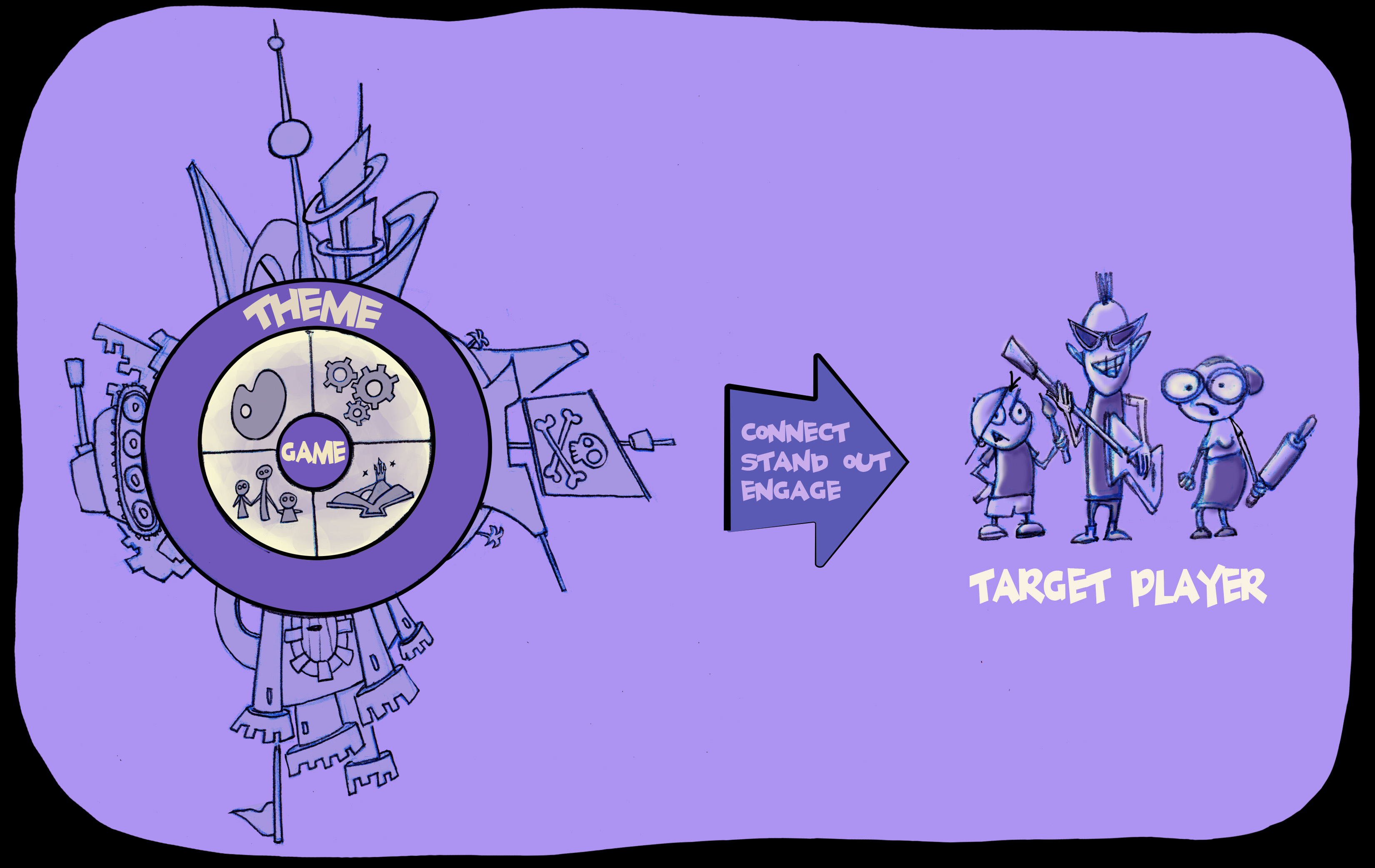

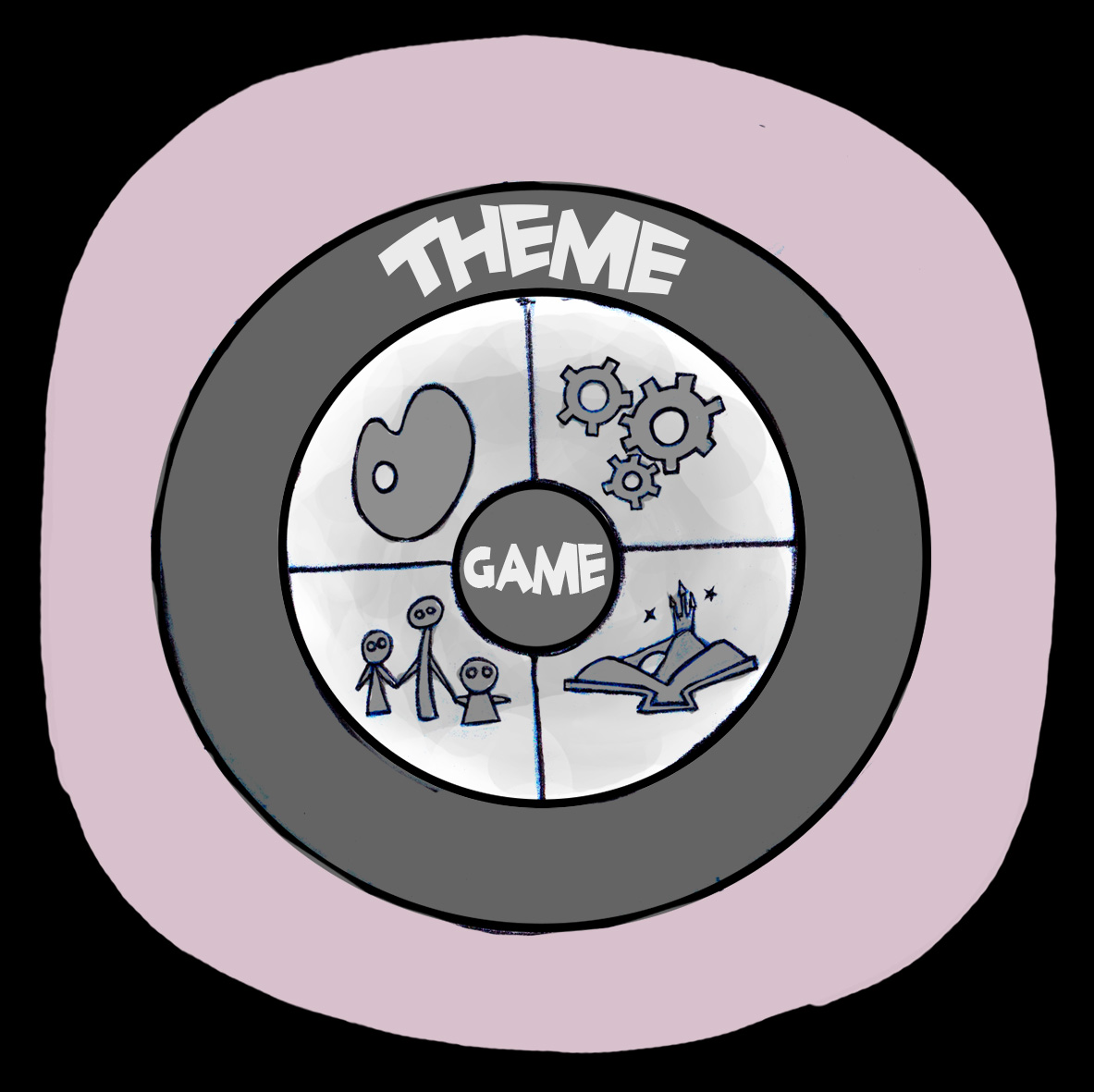

Do you feel often overloaded? I do. I bet being able to get your attention is harder and harder because your plate is already full and the requests from everywhere to fill it up even more don’t stop. Well… chances are that the people you are trying to get to play your game feel exactly the same way. It has never been harder to get people’s attention, let alone keep it, so you need to use all the tools at your disposal and a very effective one is setting the right Theme at the beginning of the development your game. How do you do that? More about that below.

The Main Goal Is Helping You Connect and Stay Connected

These days it is hard to get people to even spend the time they need to figure out if they like your game or not. Getting players interested is not about convincing them of the value of your game but about connecting your game to something they already believe or care about.

And it is not enough to connect to player’s emotions only when you first contact them. Good marketing campaigns only go so far. Players don’t recommend or spend much time or money on games that seem cool but turn out to be snoozers. To be successful you need to keep that connection to players going throughout the experience at many levels: through your art, through your mechanics, your stories, and the social interactions triggered by your game. The more elements of your game you connect with, the stronger the connection will be and the better chance you will have to keep players around, turn them into fans that help you promote your game, etc.

We actually need to do both:

1) Finding something to put in our game that speaks and connects emotionally to our players, and

2) Supporting that something with all the different elements in our game throughout the experience.

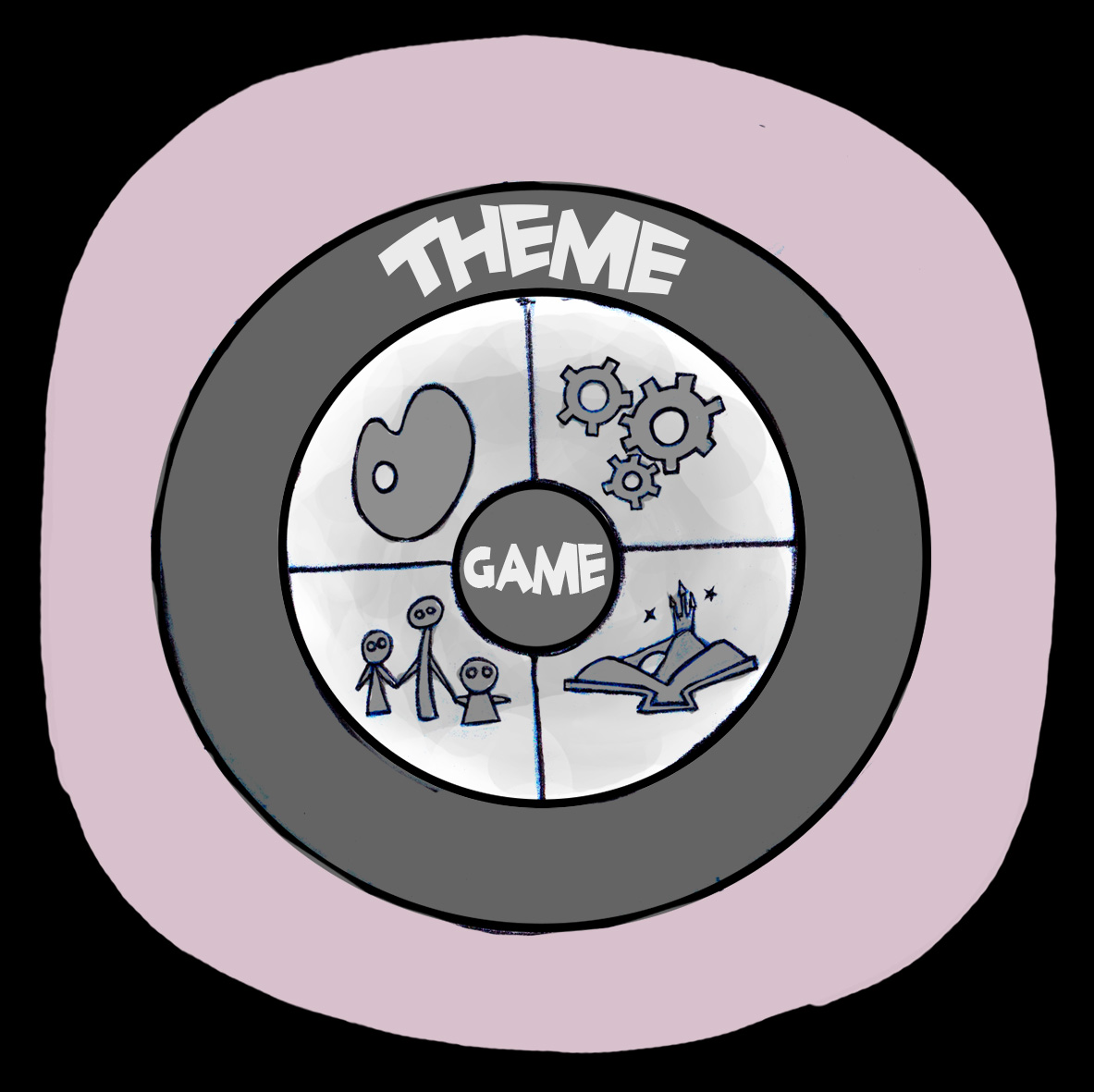

The good news is that setting up the right Theme at the beginning of development can provide the solution to both. Unfortunately, there are some very common misunderstandings about what Themes are that make them less helpful. The most common one is confusing Theme with Topic.

Effective Themes Are More Than Topics

There is some confusion on defining what Theme is. Even Wikipedia’s definition of a theme lists “love,” “death,” and “betrayal” as examples. This is a common view: when you ask a developer about the theme of their game, most of the times they will tell you their topic: pirates, space, car racing. The problem is that Topics by themselves are not that helpful in finding ways to connect to players. They rarely trigger specific emotions. Pirates? What about pirates? Is it about thugs that pillaged your town and kidnapped your girlfriend? Is it about noble outlaws fighting a corrupt system? Freedom lovers in search of adventure outside the boring status quo? Greedy and ruthless treasure hunters? “Pirates” is an inconclusive word that could trigger many different emotions depending on the context. Deciding on a Topic won’t help you figure out your game mechanics -Should you start developing a ship battling system? Treasure collecting system? Sword fighting? All of the above? It won’t help you figure out your story either – Adventure? Comedy? Romance? – Neither your art style – More cartoony? More realistic? – Nor your social mechanics -Cooperative? Competitive? Unassertive topics like “Pirates” won’t help you tie all the game ingredients together beyond the superficial either. Yes, everything will look more or less from the same time period -no cars, no cowboys, and no dinosaurs- but chances are each ingredient -mechanics, story, art, social- will trigger disparate unrelated emotions, and you’ll end up with a game that lacks focus and gets no one excited. Defining Theme as Topic is not enough.

Effective Themes Take a Stand

The definition that I find more helpful is one that I found best expressed by novelist, screenwriter, and game designer Chuck Wendig in his blog “terrible minds”: Themes are arguments; Themes are points of view about something (You can take look at Chuck Wendig’s awesome article about 25 things you should know about theme here. The article is targeted to writers, but it all applies to games). Saying my game is about “Death” or “Adventure” or “Pirates” is not defining the Theme. “Man can learn from death,” “Life without adventure is not worth living,” “A pirate’s life is a wonderful life” are Themes. They express specific opinions; they have a horse in the raise.

When you define Theme as argument it becomes much clearer what kinds of mechanics, art, stories, and social interactions will reinforce the argument. When you define your Theme not as “Pirates” but as “A Pirates’ life is a wonderful life, more fun, adventurous and free,” then you know that starting with a treasure collecting system is not the right way to go -maybe it would be if your Theme was “A Pirates’ life is wonderful because you get to be rich without working for it.” Here instead you know that your mechanics should reinforce the idea of freedom and adventure, so maybe starting with a ship system as a means to explore far away places and find adventures makes more sense. Under the same logic, you should probably avoid a rigid treadmill to level up that feels constrained instead of free, etc. Your stories should also reinforce the appeal of freedom and adventure, not enrichment, struggle, or revenge; and the same goes for your art and social interactions.

It is very common to see reluctance about stating opinions in a game for fear of alienating potential players. Expressing opinions can be scary because an opinion is always partial and causes disagreement. It is true that you will sometimes alienate some people, but on the other hand you will connect more strongly with the players that agree with you, and your game will have the appeal and personality that will help it stand out in the crowd. In fact, one of the main mistakes you can make as a developer is trying to please everybody and ending with a bland game that neither pleases nor connects strongly to anyone.

When I worked at Disney developing Toontown Online, the first Massively Multiplayer Game for kids, we decided to base the game around a common conflict most of us see in our lives, work versus play; and we took a clear point of view: play is more important than mindless work. Our point of view was the foundation to the main conflict and Theme that tied everything together. In the game, business robots called the Cogs were trying to invade Toontown, a colorful and zany place where the players -careless, playful toon characters- lived. The Cogs wanted to turn Toontown into an efficient business park and get rid of all play because they saw it as an inefficient waste of time. To defend themselves from the invasion, Toons played classical cartoon gags on the Cogs: they threw cream pies, dropped banana peels on the floor, and dropped pianos on their heads. Taking a definite stand in the conflict work vs. play was not always well received at a big corporation like Disney, filled itself with many Cog-like characters trying to increase profits at any cost, and always worried about mass appeal. There was also fear that talking about work would not resonate with kids, the main target for the game. But it turned out that having a clear point of view helped us connect with tons of players; we all have felt at some point that work is taking over our lives, leaving us with little time for fun-care-free-play. Fighting back with fun, resonates. Toontown ended up being a very successful game with a very broad appeal, liked by kids and adults, males and females. It also had much longer customer lifetimes compared to most other kid virtual worlds and MMOs. The game lasted over 10 years and remained profitable until the very end. Years after Disney pulled the plug on Toontown, me and other developers who worked on Toontown still get messages from former subscribers asking us to bring Toontown back.

Pictures Are Better Than Sermons

Taking a stand makes it easier to keep things consistent and connect to specific emotions, but remember that your game is not a sermon. You are trying to connect, not to convince. “A story is more than just a conveyance of your message” says Chuck Wendig in his article about Themes: “Overwrought themes become belligerent within the text, like a guy yelling in your ear, smacking you between the shoulder blades with his Bible. Theme is a drop of poison: subtle, unseen, but carried in the bloodstream to the heart and brain just the same.” The same is true about games. Games are not sermons and they are much better when they don’t try to be one.

One way that I find useful in keeping things in check is by defining the theme visually through creating a mood board. A mood board is a collection of a few images -should not be more than 5 in my opinion- that express the essence of the game. These images are not supposed to describe the mechanics, story or art style of the game; what they need to convey is the Theme and the emotions triggered by it. Since images can be interpreted in different ways, the visual mood board makes it hard to focus on lecturing and easier to focus on a consistent set of emotions tied to the Theme.

I think Themes are some of the most powerful tools to help you connect emotionally to players and glue together more consistent and stronger experiences. Have you been in a project where the right Theme saved the day, or the wrong one sunk the ship? Let me know in the comments.

Added on 6 February 2017

By WpFlara!-14?!

1 Comments

Adding storytelling to your game can help you connect emotionally to your players, add meaning to the experience, and increase long-term engagement. But stories can become more of a nuisance if not implemented properly. Following a few rules of thumb will help you add storytelling that does not clash with the rest of the experience.

Why Story

As I mentioned in a previous article, a combination of good art and fun game mechanics is a very effective way to attract players and create immediate engagement. But even good game mechanics can get repetitive and tedious over time unless they are accompanied by a larger meaning or drive, which is often provided by other elements like story, and social connection.

Events are much more meaningful if they are tied to a larger story. When playing basketball, scoring a basket is fun, but the experience is much more meaningful and powerful if that basket is the winning basket at the end of a game against a long-time rival team, even more if winning will let us get a scholarship to a renowned college… and will make us the first in our family to get a college degree… which will eventually let us to help our family get out of poverty and… you get the idea.

What is so powerful about stories is that they can wrap up the combination of ideas and emotions that form our experiences in ways that we can easily understand and link to our values and other experiences in our lives. A story can turn an abstract goal into something that relates to our values and views of the world.

Here are 3 rules of thumb to help you determine if you have a story that works to make your game more compelling without annoying players:

Rule of Thumb 1: Start with a Clear Conflict

There is one single element that fuels a good story: conflict, says Evan Skolnick in his excellent book “Video Game Storytelling, What Every Developer Needs to Know About Narrative Techniques.” He is right. Story is not a lot of blah blah blah, it is not fueled by details about characters, feelings, and places, it is fueled by conflict, by someone wanting something and not being able to achieve it because of something else. Make that conflict clear as soon as you can in your game.

The more your players can relate to the story’s conflict and to what is at stake, the more compelling your story will be for them. The faster you can introduce your players to that conflict and why it matters, the sooner the easier it will be for them to find meaning in the activities and goals they need to complete.

The conflict you show your players first doesn’t need to be the only one. It doesn’t even need to be the main one, but it should be the one that helps the player makes sense of what he/she needs to do in the game next.

Rule of Thumb 2: First Do, Then Show, Then Tell

There is an old axiom in Hollywood that says: “show don’t tell.” If you want to communicate how courageous a character is, don’t say it, instead show the character doing something courageous. In the same book for video game storytelling I mentioned above, Evan Skolnick says that in games, where the players are active participants, this axiom can be modified to: “do, then show, then tell.” If you want to communicate how courageous and powerful a character is, give her powerful abilities and give her big challenges to face, instead of telling the player the attributes of her character, let her can experience them herself.

If you cannot find a way to communicate story through actions, then use visuals as a second option, and only if there is no other way of conveying important information that your player needs in order to make sense of what she is doing, say it through dialogue or text.

Rule of Thumb 3: Keep It Simple and Minimal.

The right story makes the game more intuitive, but to do that it needs to be simple. It can get deeper and more complex as the game progresses, but their primary goal is to make your game’s goals and rules easier to connect with and easier to understand. If the story is not making it easier to play, chances are it is not the right story.

The story should also be kept at a minimum. One of the main mistakes that game developers make when adding story is trying to communicate at the beginning of the game all the background of the story to the players. Players do not care about your story details or your characters until they are more invested in the experience as a whole. It is important to provide meaning, but you don’t have to provide the player with more information than the bare minimum to make your immediate goals and activities make sense. The worse thing you can do is present and player with a bunch of information that they don’t yet care about. Long dialogues and explanations are usually skipped and all your work will be in vain. Start simple, and add complexity only if the rules and goals of the game require it.

Evan Skolnick divides story facts into 3 categories: first, facts that you need to know right now to understand what you need to do in the experience; second, facts that will be important later in the experience but you don’t need to know yet; and third, facts that maybe add flavor but are not essential at any time in the experience to understand what you need to do. As a rule, the only information you really need to give the player is the one related to the first category. Save the rest for later and even then try to convey it first through actions and visuals.

Chess

Let’s look at Chess as an example. It maybe an extreme case but I think it exemplifies the points that I am making. The conflict is simple and easy to understand: you are a king with a court and an army, your enemy is another king with his own court and army and you need to defeat him. There are other details in the story about who is in your court, which characters are important and powerful, how big is your army, etc., but all that information is communicated through actions and visuals. You know who is your enemy because your team is one color and your opponent is the opposite color. You know that there are different characters because your pieces have different shapes. You know who is in your court and how powerful they are because your different pieces have different attributes and behaviors, and some of these attributes prove to be more powerful. The story is simple and minimal. It helps us make the rules and goals of the game more intuitive; like the fact that only knights on horses can jump other pieces, or that the most important piece is the king, but it does not give us additional information that is not essential to understand what to do next.

Conclusion

Story is an important tool to help us add meaning and connect emotionally to an experience. But the wrong story could turn into an annoyance to the player. By following these 3 rules you can avoid wasting time and resources developing stories that don’t help your game: 1) Introduce a clear and easy to understand conflict as soon as you can. 2) Communicate your story through actions first, visuals second, and only as a last resort through dialogue and narration. 3) Keep the story simple and minimal, give you player only the information than helps him/her understand what he/she needs to do in the game at that point.

Added on 4 January 2017

By WpFlara!-14?!

0 Comments

But Don’t Make This Mistake:

“The best content is other people” says Dmitri Williams in a recent op-ed article in the L.A. times, making a very good case about the importance of the social aspect in helping new games and platforms succeed. But for social features to work, they need to happen at the right time and place in your experience.

The most successful games of the last few years have all helped us connect socially: “World of Warcraft,” “League of Legends,” “Pokémon Go”. Creating a community not only brings new content but let’s you grow your game or platform organically; a vibrant community is a very strong attractor of new players. This is why it is so important for games and new platforms like Virtual Reality to figure out how to add social components. “Virtual Reality needs to be social to succeed,” also argues Signe Brewster in another great article making the case for social, but the importance of forming a community is not limited to VR: it is an essential ingredient to any game and app that is trying to engage people in the long-term. We are social animals. We like to feel connected to other people and feel part of something larger. The trick is that the features that will help you build a community need to come at the right time and place. Otherwise they won’t work.

A very common mistake that I see many developers make is underestimating the cost of social features. I am not talking about production and implementation costs, although that could also be expensive, but high costs from the player’s perspective: our social status is precious and we are very protective of it. Many games ask us to invite friends and post about the game in our social networks as soon as we finish a couple of levels. Do you do it? I doubt you do. I don’t.

The reason is because social interaction is expensive. Our social standing among our friends and family is precious; we are not willing to mess with it easily; even less for something that we don’t care much about. Most players are only willing to share things that they are committed to and believe will help their social status. They won’t share just because it is easy to do, or by giving them a cheap incentive. In a way we deal with these things in a similar way we deal with other things in life. We would not introduce a person we just met at a bar the night before to all our friends and family in Facebook, even if we had a good time at the bar. The same goes with your game, not many are willing to share after the first few sessions; you are better off focusing first on creating an experience that players will find worth sharing, and leaving the social aspect for later in the game experience. Once you are deeply invested in an experience you are much more willing to try to bring your friends along.

The same thing happens with multiplayer games like MMOs. Even if it is not about bringing external friends but about meeting players and making friends inside the game, most people rather play alone until they have mastered the basics of the game. Most people don’t want to appear as incompetent, even in front of strangers. So here too, you don’t want to introduce social features and social pressure too soon. This will also be the case for any social VR apps out there. Social is powerful, but to really thrive people need to feel safe. Social mechanics work better when you are already familiar with a space and its rules, when you already feel competent and confident. This is what successful MMOs do well. When we designed Disney’s Toontown Online, we pushed players to make friends with other players in specific missions, but those missions were only available after you were familiar with the world, and they provided very clear objectives that worked as ice-breakers. The reason it was easy to make friends and form a larger community is because you had a clear excuse -a mandate to connect- and the connection benefitted you and your new friends and made everybody more successful in the game.

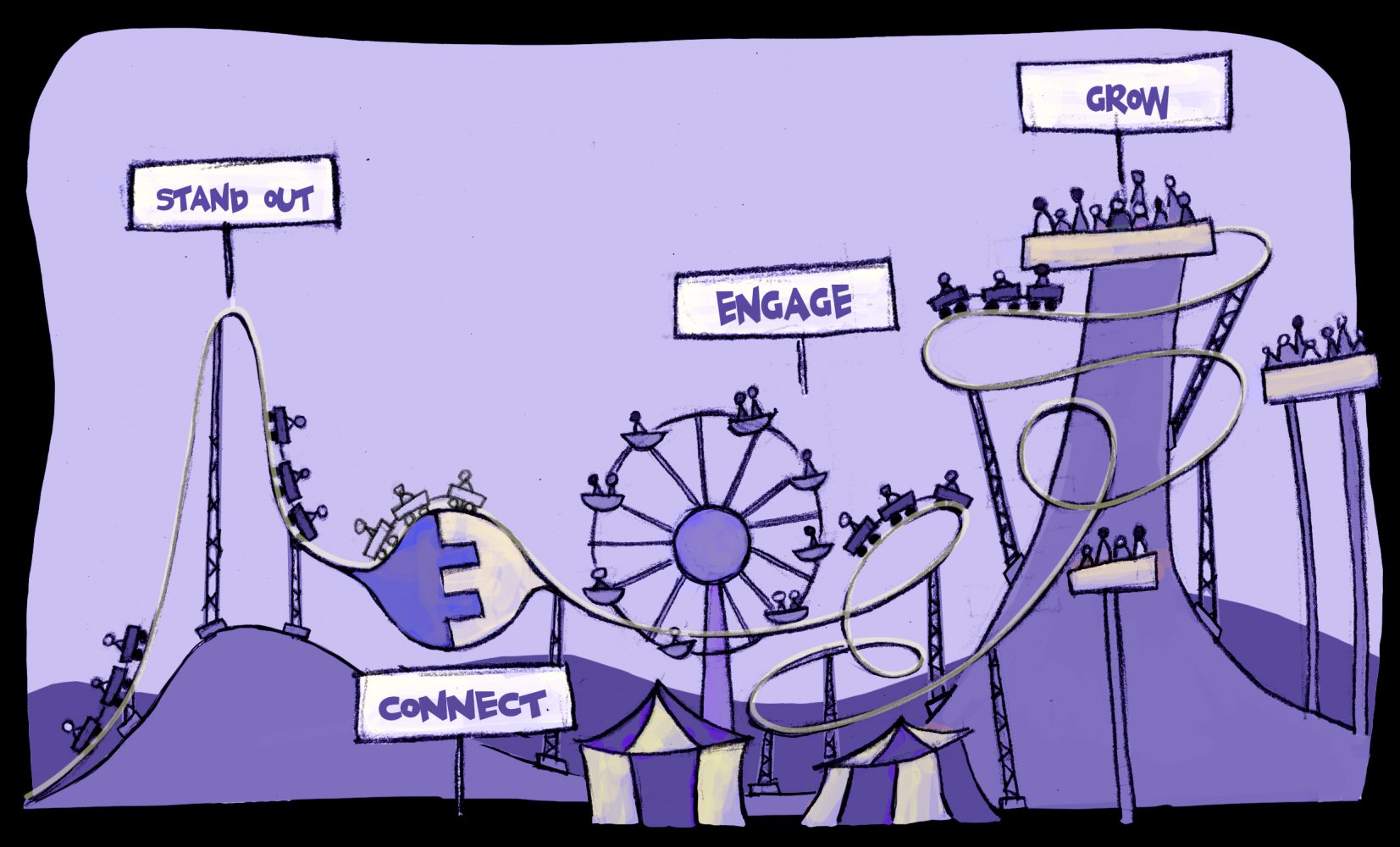

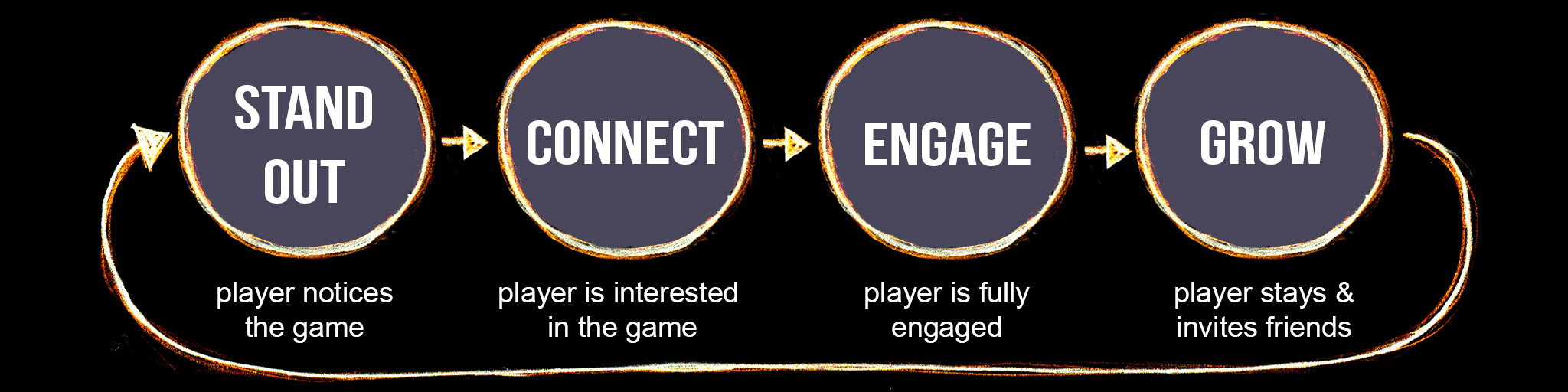

In a previous article, The 4 Steps of Successful Games and VR Experiences, I talked about the steps of long-term engagement: stand out-connect-engage-grow. First you need to stand out in the crowd of games and apps; then you need to connect emotionally to the players so they are willing to give your game a chance; then you need to find ways to keep them engaged; and only then you can bring the social aspect to help grow your product. Even in the case of MMOs where social interaction is key, it is better to limit and scaffold around the social aspects until your player feels like she has mastered the game enough to have a good social standing.

Before adding social mechanics somewhere in your game, ask your self a couple of questions to figure out if your player is ready for them:

- Is the player already engaged? Make sure that the metrics you are using to determine that your player is engaged make sense -finishing one level of your game does not mean the player is engaged.

- Does the player feel confident about the rules of the game and his/her role in it? Will socializing help her strengthen her social standing? If not, how can you scaffold your game’s social interactions so they feel safer and risk-free?

Conclusion

Social features are very powerful, but they are also precious for most people. Adding social features too soon can backfire. Most players need to be fully engaged and feel comfortable before they are willing to interact with strangers or they are willing to bring their friends over to a new experience. I strongly believe that if you want to engage players in the long-term it is crucial that you include some community building features; but make sure you engage and make your player feel comfortable first.

Added on 1 December 2016

By WpFlara!-14?!

1 Comments

How can you make your game more engaging and effective? In a nutshell, by making engagement stronger at the different levels of the experience and by making engagement connect to your ultimate goals: monetizing, teaching, or changing behavior. There are 3 questions that can help you figure out how to best do that and they can be applied not only to games, but also to education, VR experiences, and other software that needs to engage users. Let me elaborate.

I talked in a previous article how successful games and experiences need to first stand out so your target players notice you, then connect with them at an emotional level so they are willing to give you a few minutes of attention, then engage them so you can keep them for longer time, and finally get them to help you grow by sticking around and inviting their friends to join in (more about this process in this article here). To do that, games can use different ingredients like compelling art, fun game mechanics, resonating themes, etc. Some ingredients like art are better at helping you stand out, some others like mechanics are better at keeping engagement going (more about the ingredients in this article here). The challenge is how to mix and tie these ingredients together to take players to full-long-term engagement.

Game design is an art and a craft that can take years to master, so I don’t want to oversimplify the art of engagement, however I find that the following 3 questions can often bring good clues about what is missing and possible solutions to make the game more successful at reaching the goals we want.

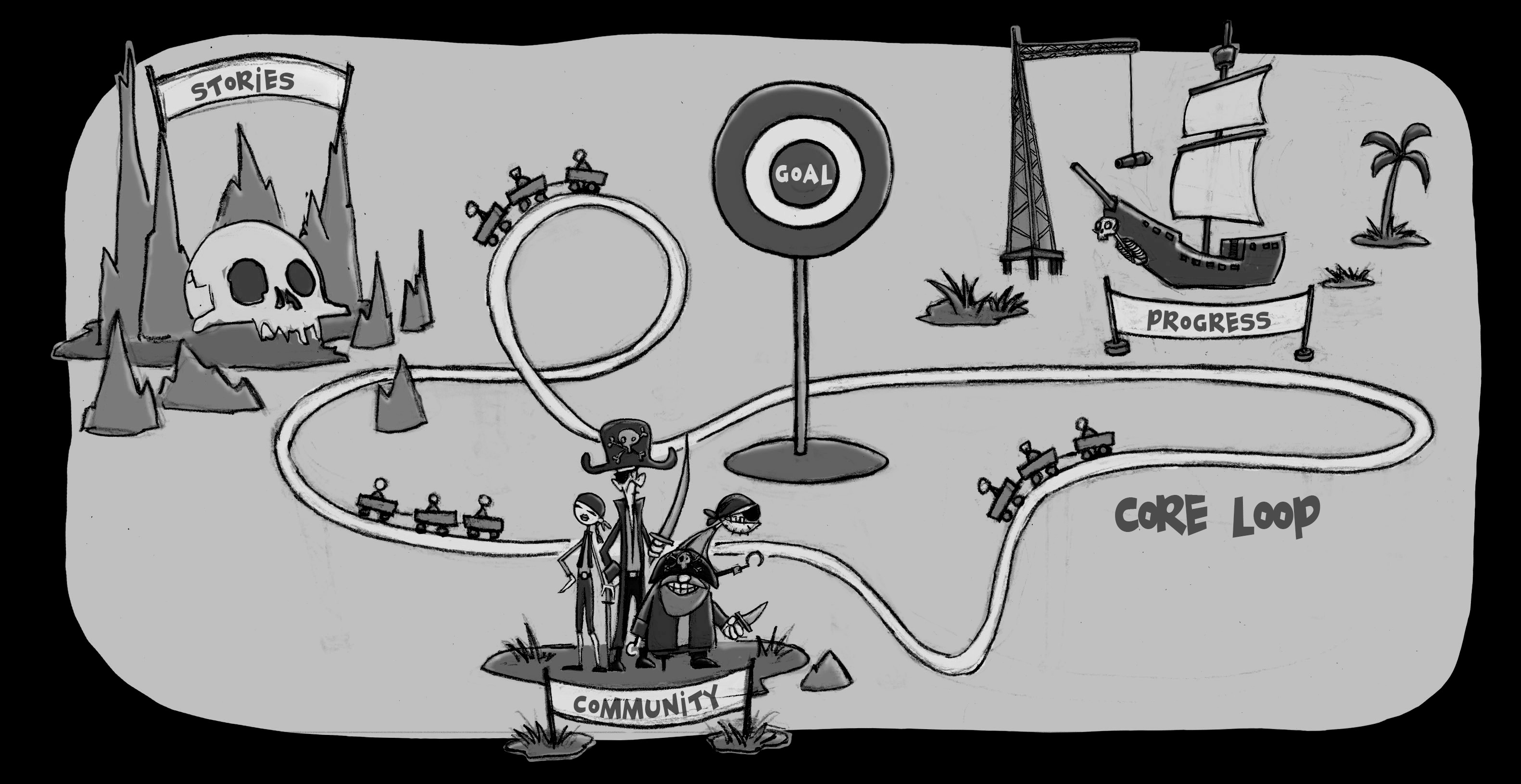

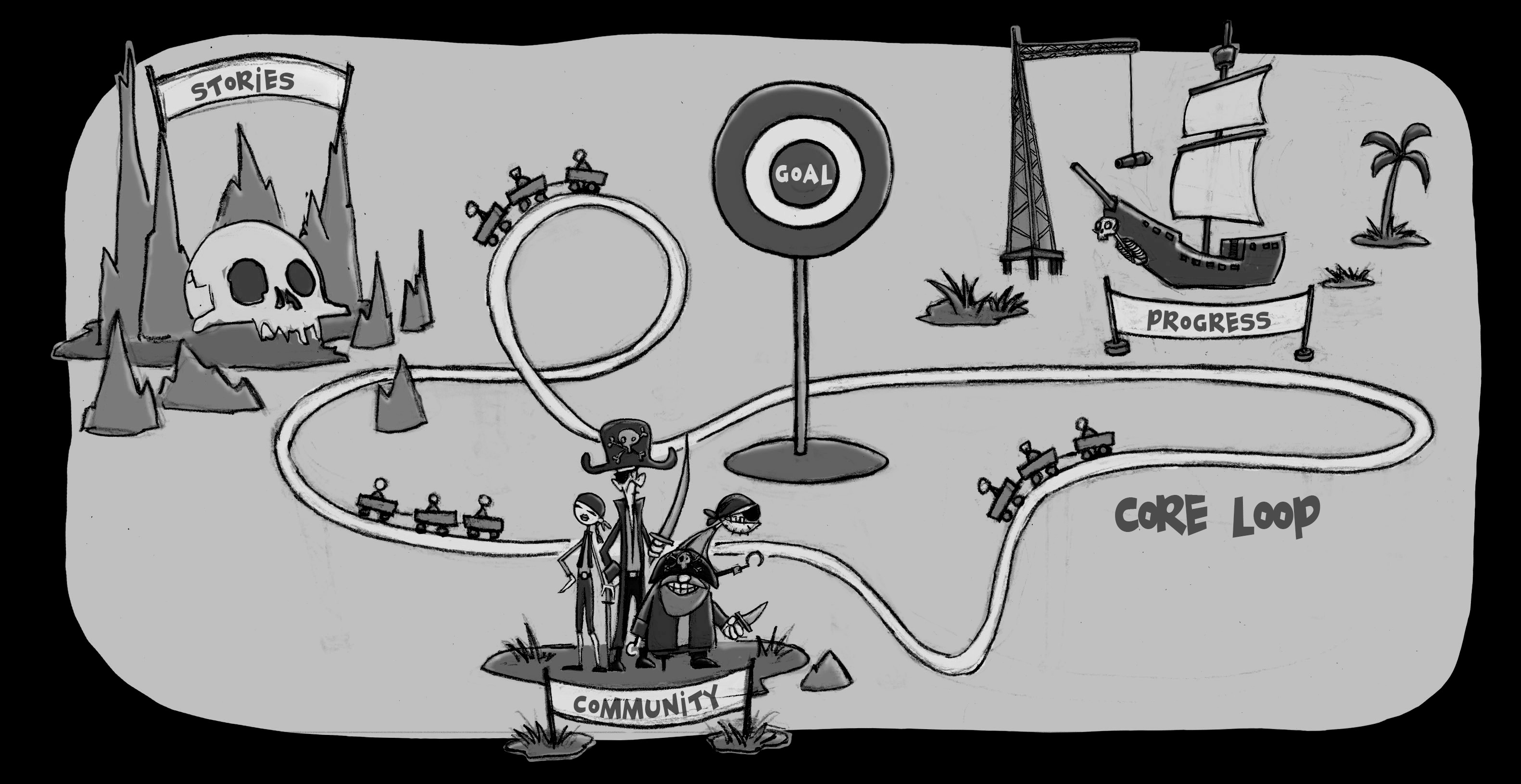

Question 1: Do You Have a Compelling Core Loop?

All games have a core set of activities that the player repeats over and over to advance through the game. These core repeatable activities are usually called Loops. Clarifying what is the core loop in your game and analyzing it can be very enlightening in finding out why your game works or doesn’t work.

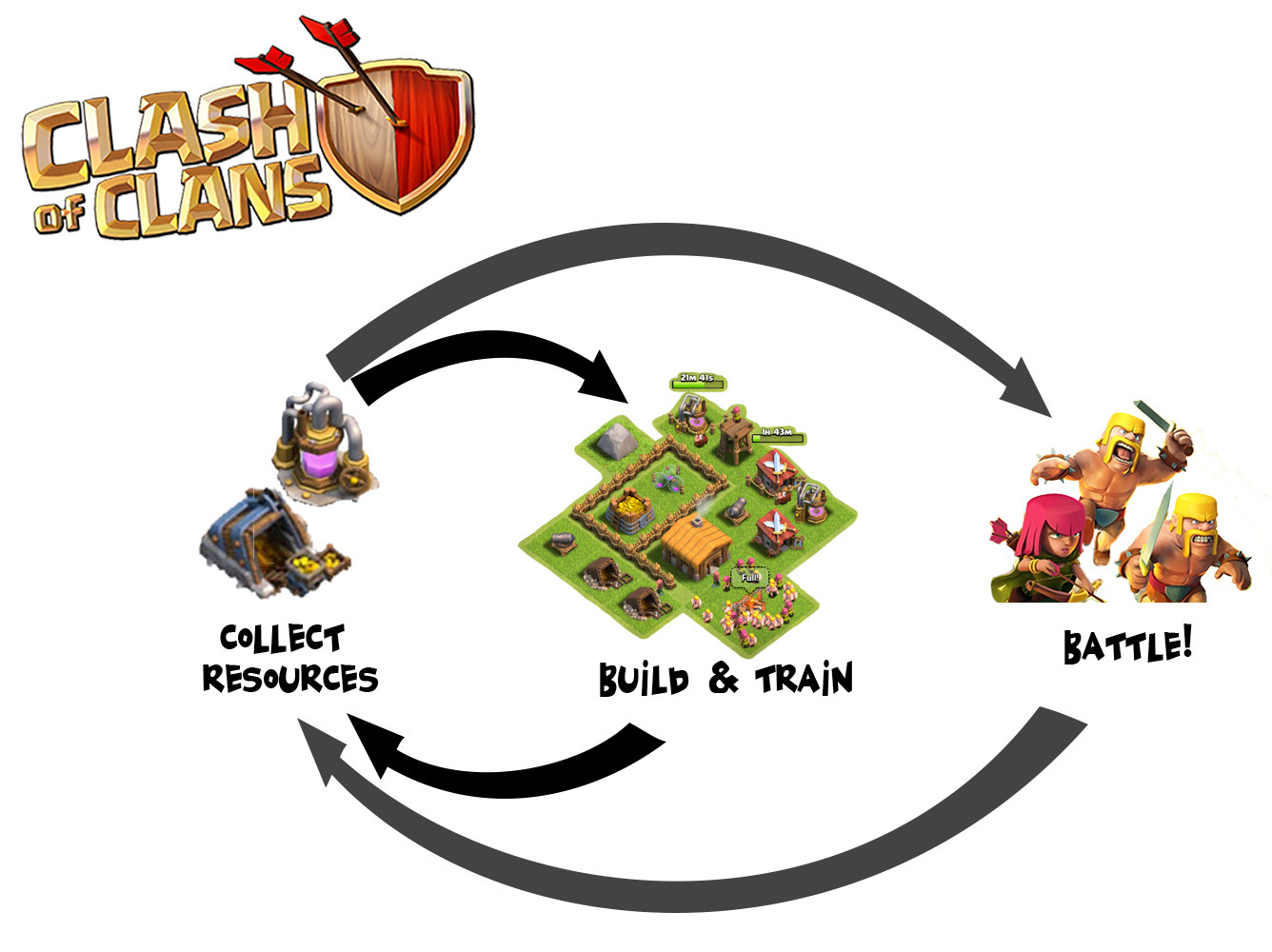

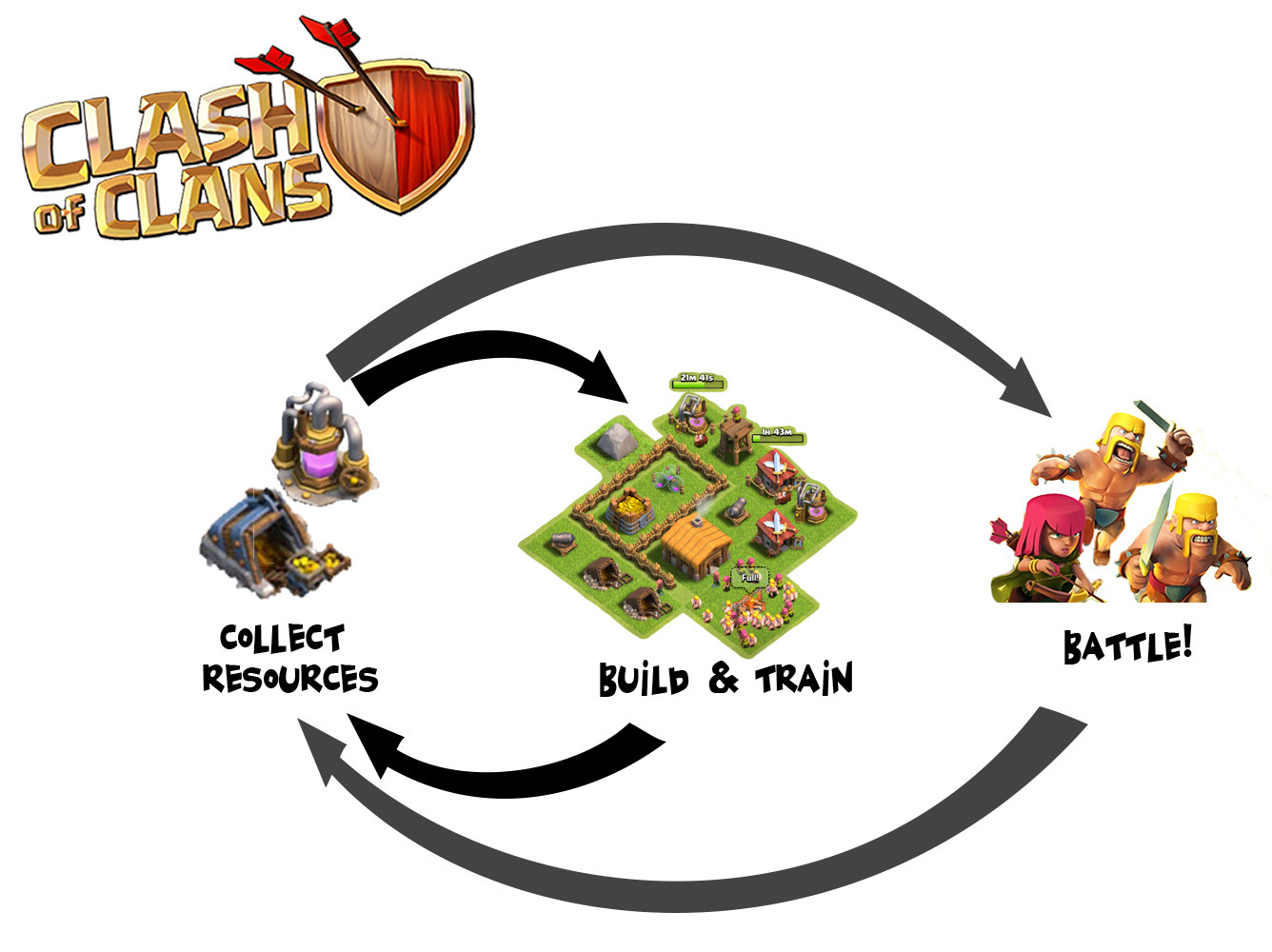

Games like Clash of Clans have perfected the use of loops to keep players engaged for a long time. At a basic level the loop is pretty simple:

You complete rewarding activities that compel you to come back and do more rewarding activities. Game designer and start-up consultant Amy Jo Kim identifies 3 rules that core loops need to follow to drive re-engagement:

- They have a set of compelling activities. In Clash of Clans these activities are all related to building up your village and battling other villages.

- Those activities give you positive feedback that make the completion of activities much more satisfying. This feedback makes you feel that you are getting better at something and getting rewarded for it. In Clash of Clans, as your village grows and as you defeat other villages you get access to more resources and better troops.

- Built into this cycle there are triggers and incentives to keep you going back to the game. In Clash of Clans all the building up, collecting resources, and troop training takes time, so there is an incentive to keep coming back to reap the benefits of what you have already done. Also, as you put more time into developing and customizing your village and improving your troops, you feel more invested in the experience, which makes you want to go back again.

I think her analysis is very useful and provides useful sub-questions to identify potential problems and opportunities with your core activity loop:

- Are the activities in your core loop compelling enough? How can you make them more compelling?

- Are you giving your players enough positive feedback about the activities they completed? Do they feel they are progressing and mastering a new skill? How can you amplify that positive feedback?

- Does your loop have triggers that pull players back into the game? As they go through the loop, do players feel more invested in the game? Can something be added to lure players back? Can something be added to make players feel more invested?

If you want to go a little deeper on how these 3 rules work in different loops, take a look Amy Jo Kim’s article here.

Question 2: Is Your Core Loop Tightly Connected to Your Goals?

Connecting your core activity loop tightly to your goals is key to making a successful game. There are many for profit free-to-play games that don’t sell enough items to even be sustainable, and many educational games that are not very good at teaching what they were suppose to teach. Some are even fun, using proven fun mechanics copied from other successful games, but unsuccessful at connecting those mechanics to their goals in any meaningful way.

If you are trying to sell items, those items should enhance your core loop experience. A successful example of connecting your loop to your goals is Pokemon Go. In Pokemon Go your beginner core activities are basically three: 1) walking around searching for Pokemon; 2) catching the Pokemon you find by throwing PokeBalls at them; and 3) walking to PokeStops to get more PokeBalls and other items that will make it easier to catch Pokemons. At first you have enough PokeBalls and catching Pokemons is very easy, but as you level up you will find higher level and harder to catch Pokemons that will need many more PokeBalls to be catched, so you will easily run out of PokeBalls. You can always walk to a PokeStop and get more PokeBalls, but since you are already somewhat invested, spending $1 to get extra PokeBalls doesn’t sound bad. You could keep playing for free by continue walking around to different PokeStops, but by spending $1 here and there you can make your play much more convenient and increase your chances of catching rare Pokemon faster. The items that you can buy directly make your core loop easier, so even if the game does not force you to buy anything, many players end up spending a few dollars here and there to improve their experience.

In the case of an educational game, that set of core activities should produce learning. In her article Why Games Don’t Teach, Ruth Colvin Clarke talks about some examples where the game activities do not align with the educational objectives, which makes the games very ineffective. She presents some experimental evidence that concludes that narrative educational games lead to poorer learning and take longer to complete than simply displaying the lesson contents in a slide presentation. One of the games she tested is a game called Cache 17, an adventure game designed to teach how electromagnetic devices work. The problem with this game and the other games she mentions in her study is that the games’ core loops are only vaguely related to the topics they are supposed to teach. In the case of Cache 17, the players need to solve a mystery about some missing paintings that disappeared during World War II by searching through an underground bunker. The link to the topic is that players occasionally need to build an electromechanical device to open some doors and vaults in the bunker. The core loop is about exploring a bunker and finding clues, not about experimenting with electromechanical devices. Not surprisingly, the study found that reading a slide about electromagnetic principles was quicker and much more effective at teaching the topic than playing the game.

When the educational objectives are more aligned to the core loop the results are very different. Using a resource strategy game like Sid Meier’s Civilization as a supporting tool to teach the relationships between military, technological, political, and socioeconomic development has been so successful for educators, that a purely educational version of the game was announced for 2017. Here, the core loop is closely aligned to the educational objectives. Your core play is all about figuring out the right combinations economic development, exploration, government, diplomacy, and military conquest to create a successful civilization.

Question 3: Is Your Core Loop Connected to All the Ingredients of an Engaging Experience?

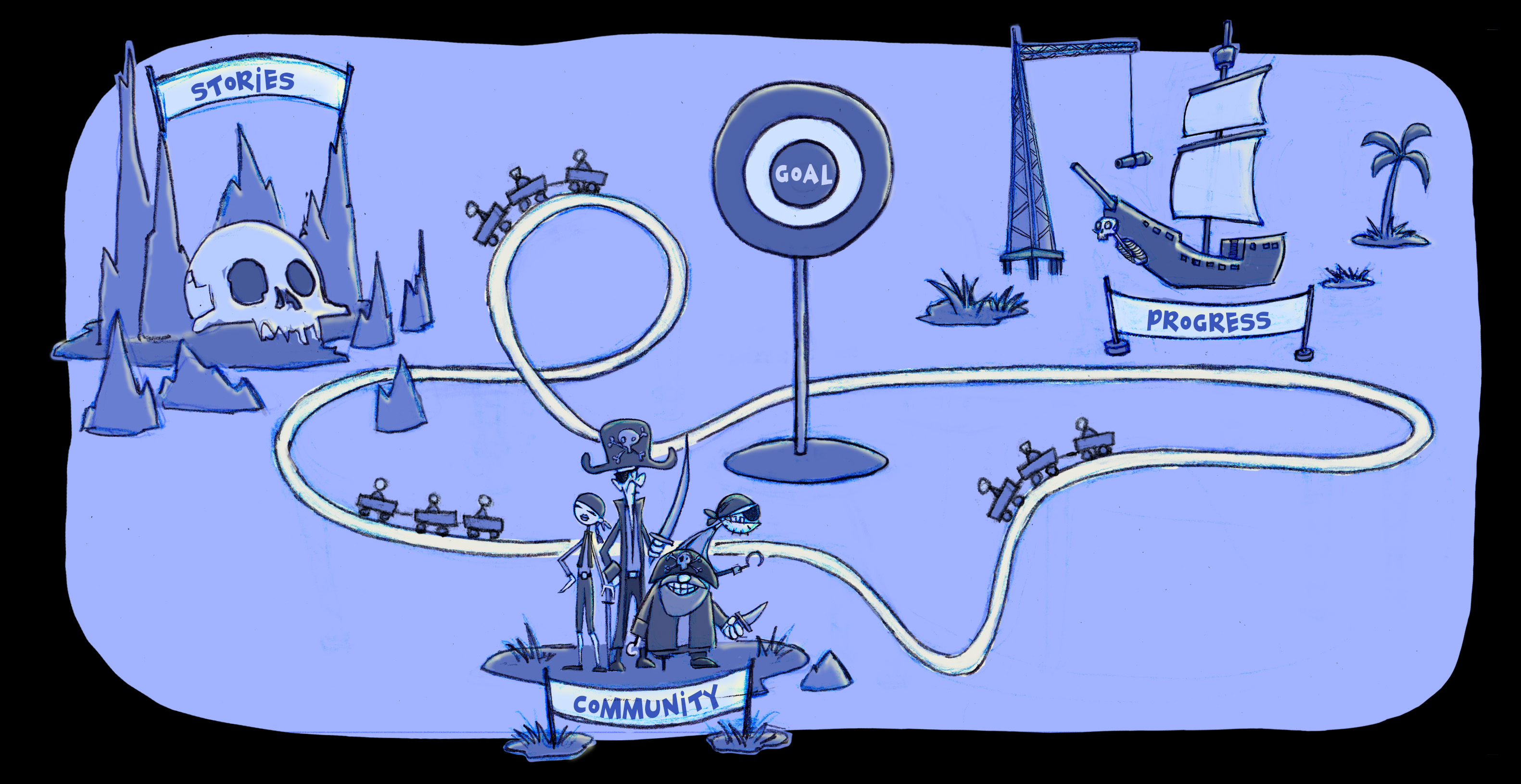

As I’ve mentioned in a previous article, the ingredients of engagement go beyond game mechanics; they include other things like art, theme, story, and community building. When you are able to connect your loop to these other ingredients the engagement is much more powerful.

In Toontown Online for example -a game developed by Disney in which the overall goal was to defend a cartoony world from invading business robots- we wanted to make sure that the core loop reinforced the overall Theme of the game. This Theme was something like: “Work is always trying to take over our play time, but play most prevail” so we included as an essential part of the core loop to stop the robot invasion the need to play. Without playing arcade-like minigames you could not earn jelly beans, the main currency that was essential to buy gags that would help you stop the business robot invasion. So even when the story and main conflict was about defending Toontown and battling business robots, you couldn’t do it without playing and having care-free fun. The result was a core game loop that reinforced the Theme of the game, the conflict between work and play, and because the Theme resonated with many players beyond our original target -kids between 6 and 12- the game ended up being very popular with players well beyond our target demographic. Also, as you repeated the loop, the game prompted you to explore other parts of the world, team up with other players and make friends, and unfold new stories. In other words it pushed you to discover new art and stories, build community, and master the mechanics, which made the game much more engaging. The result was an average player lifespan much higher than most other family oriented games at the time, which made the game very profitable for over 10 years.

The more you are able to connect your core loop of activities to the ingredients that make a game engaging, the stronger and longer engagement you will have.

Conclusion

Clarifying what is your core activity loop is a powerful tool to make your game or experience more engaging. Once you clarify your loop, these three sets of questions will help you shortcomings and opportunities to make your game more engaging and successful:

- Are the activities in your loop compelling enough? Do you provide enough positive feedback when players complete the activities? As players complete a loop do they get something that makes them feel invested?

- Is the loop directly linked to your objectives? If you are selling something, does that make the loop more satisfying? If you are teaching something are the core activities directly linked to the topics the player needs to learn?

- Does your loop reinforce the different ingredients of an engaging experience? As players go through the loop, can you provide more things to discover and get mesmerized by? Can you add more interesting pieces of a story? Can you guide the player into forming a tighter community?

Do these questions trigger for you new ideas on how to improve the game you are working on? Please let me know in the comments.

What makes a game successful depends on your goals, sometimes it is revenue, sometimes it is number of downloads, impact on your players, etc. However focusing on these outcomes is usually not very helpful as a developer, it is much more helpful to define success in terms of engagement because engagement can be linked directly to the kinds of decisions we need to make during development.

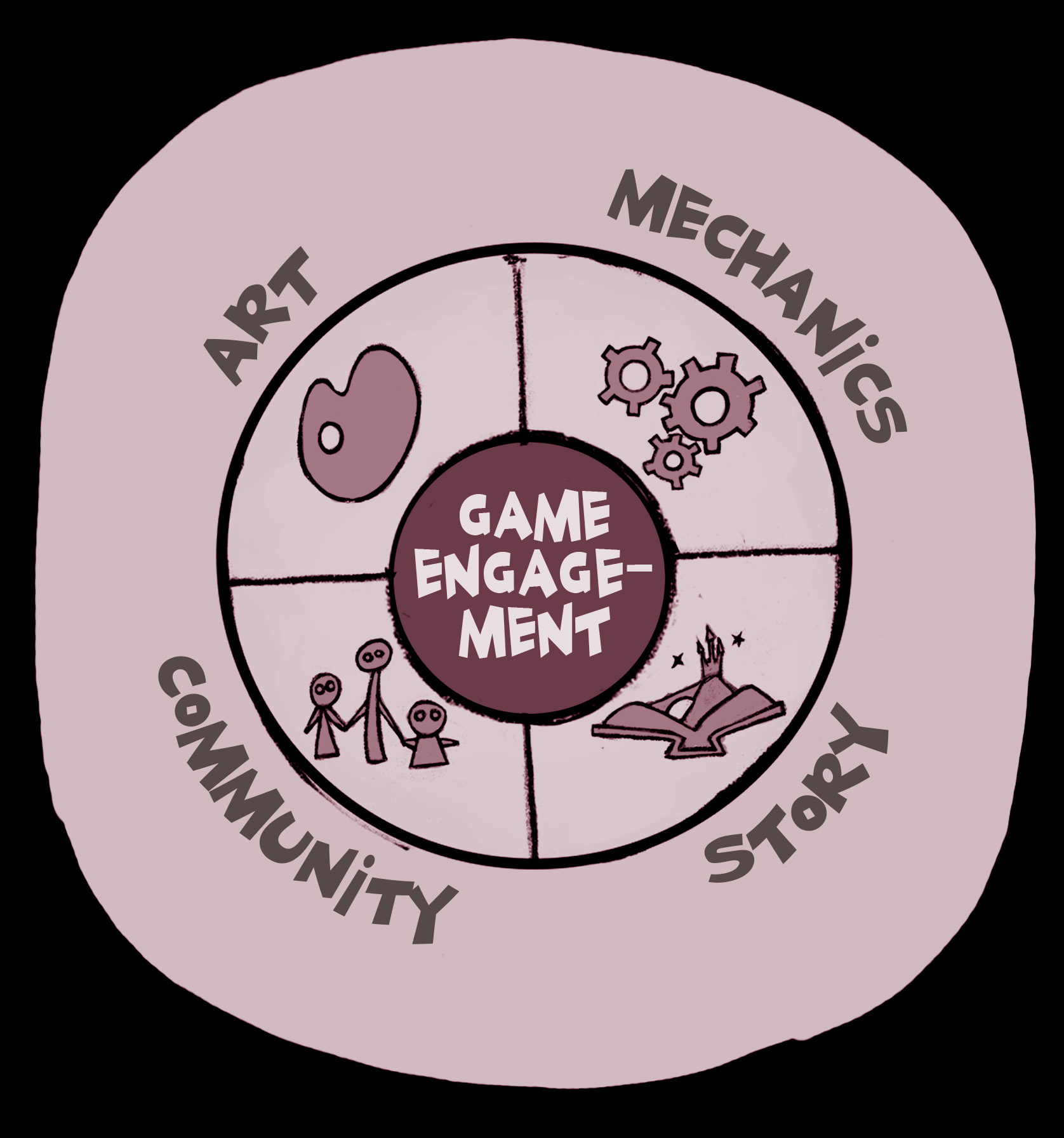

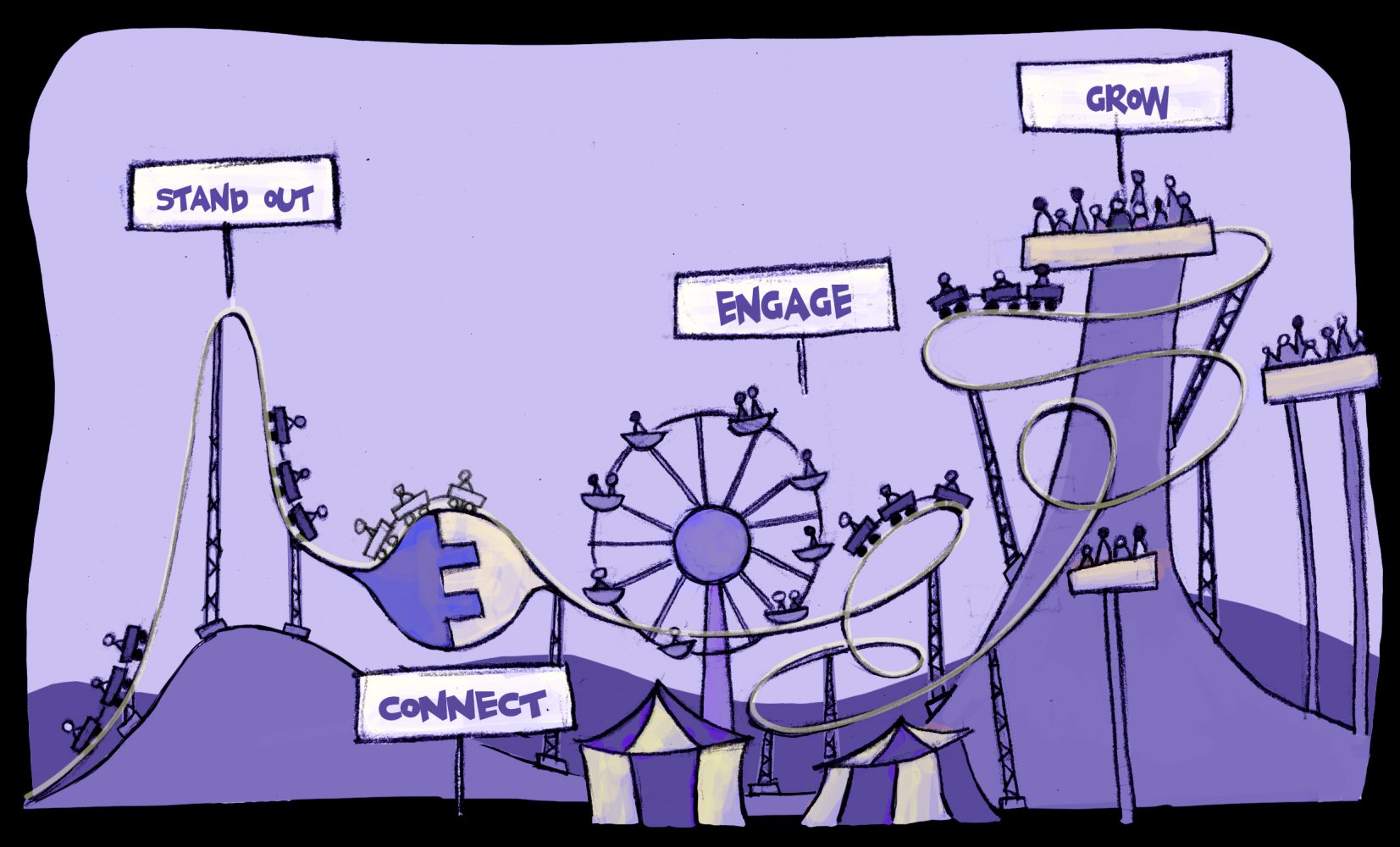

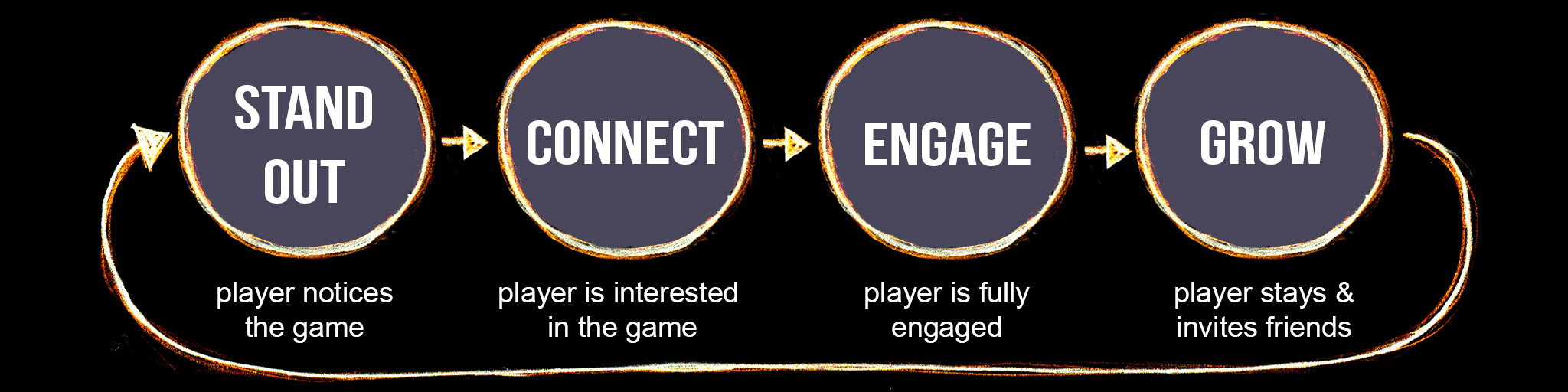

In a previous article I mentioned how engagement follows a 4-step sequence: stand out, connect, engage, and grow. The next step is to figure out what are the ingredients in a game that can help you do that. In this article I am going to talk about 5 ingredients that will help your game or VR experience be more engaging in the long-term.

Your Ingredients

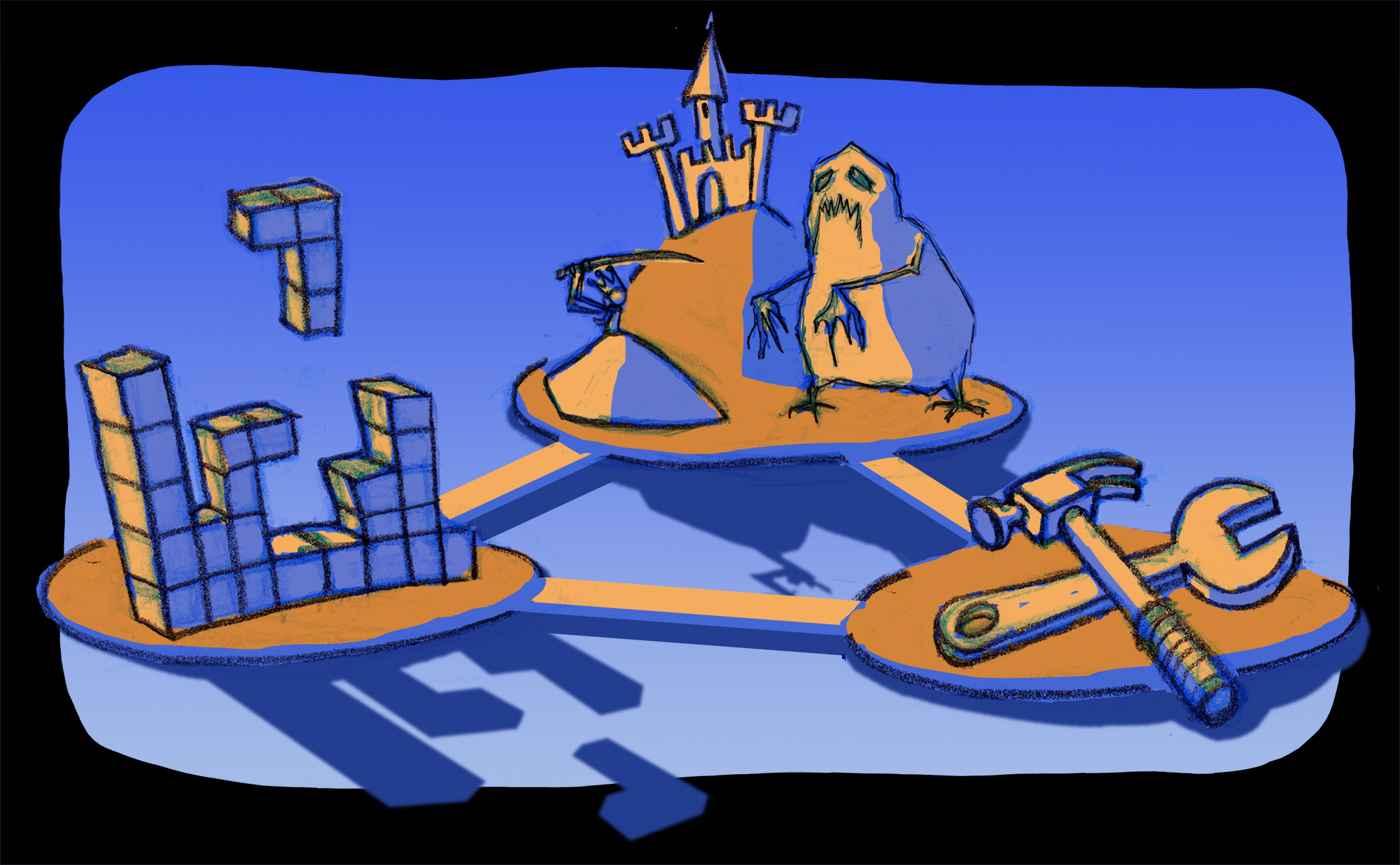

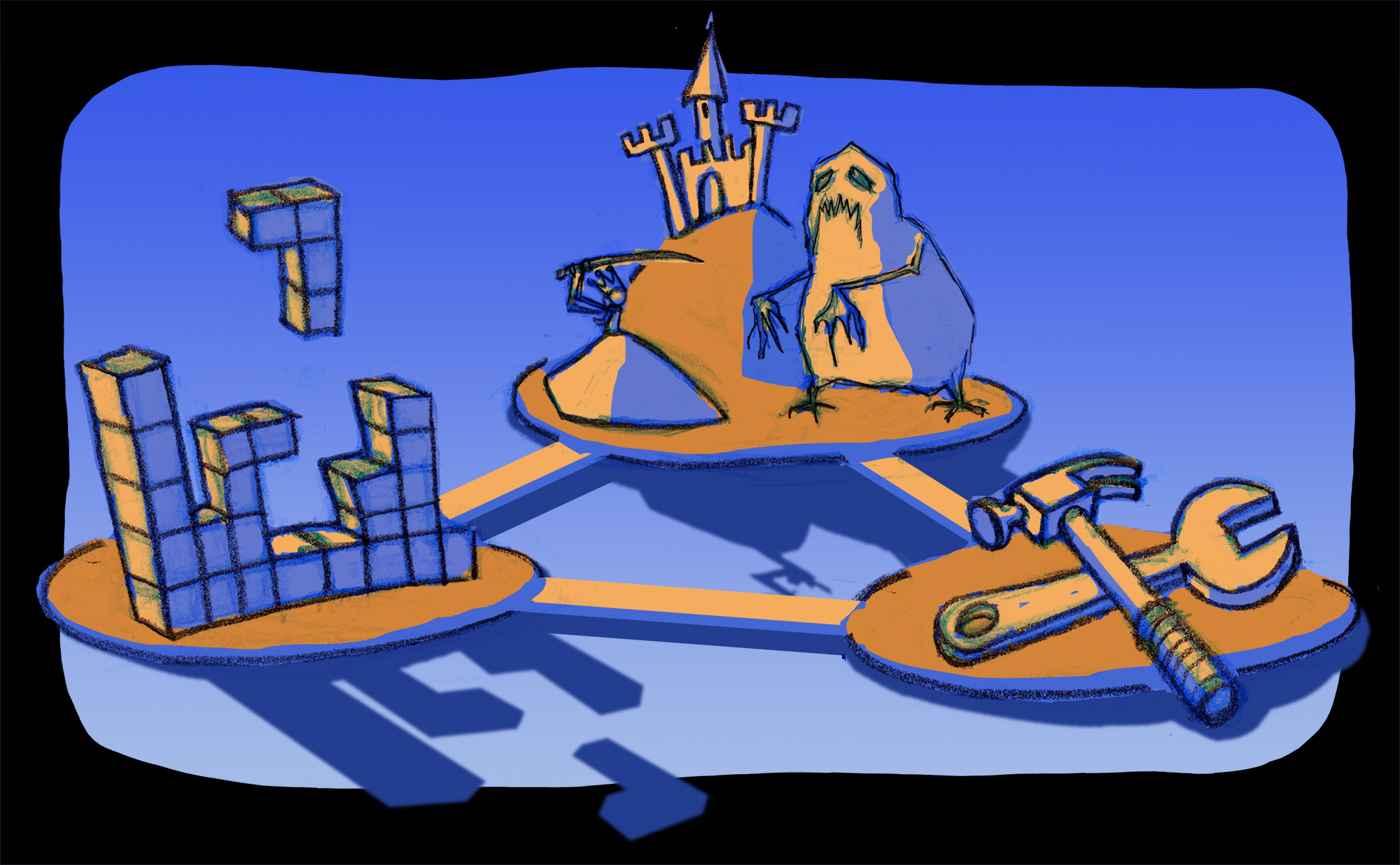

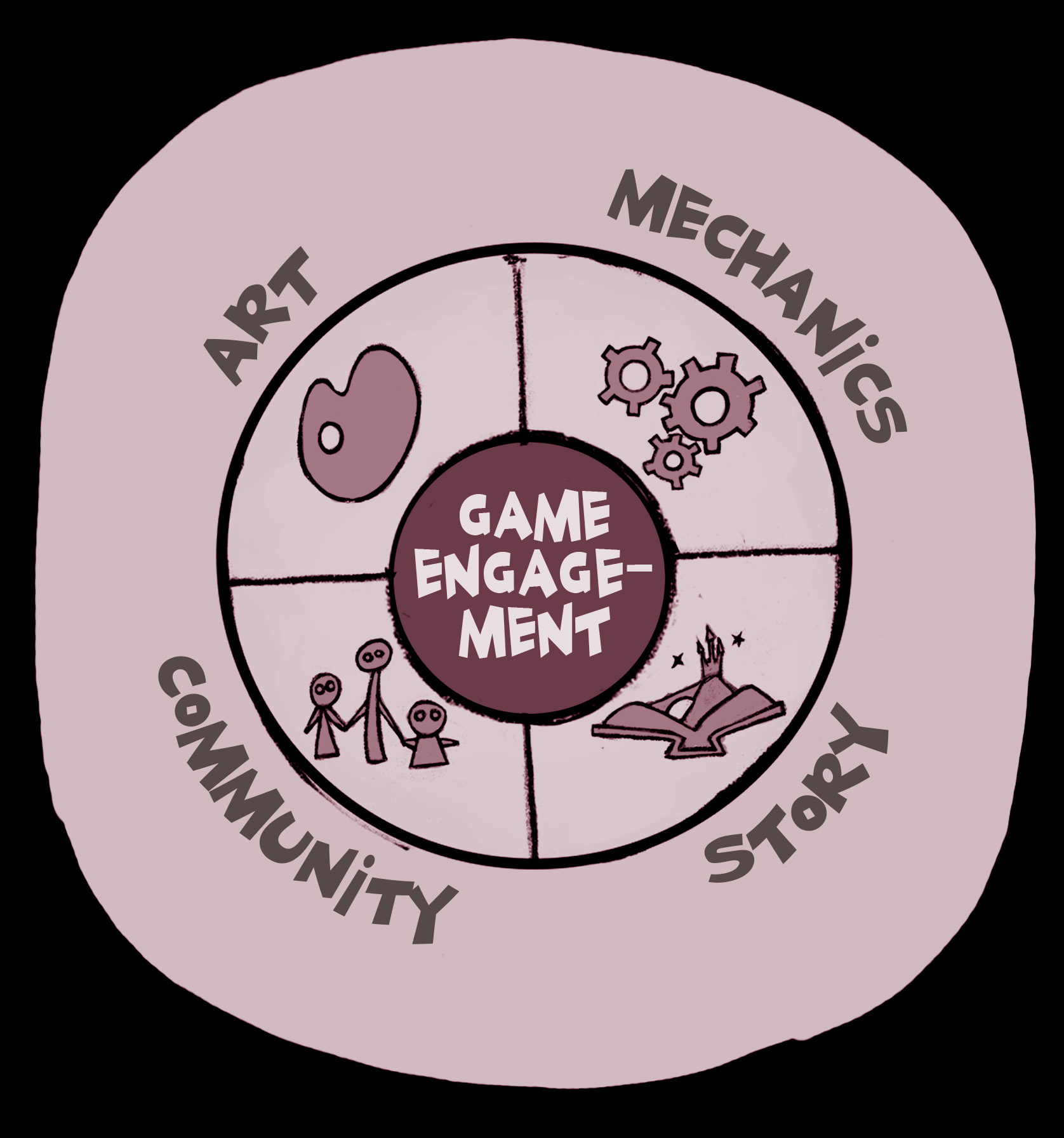

In the many years I spent developing MMOs for casual gamers – kids and families- I saw how there are four basic elements that can be combined very effectively to get the attention of players and have them stick around: art, fun mechanics, story, and community building:

- ART – Art is what first catches your players’ eye and makes them want to take a closer look at your game. At first players won’t know much about the specific mechanics and stories in your game, it is through visuals that resonate with them that they decide to pay more attention.

- FUN- But art by itself, no matter how cool it is, won’t keep your players for long. Finding fun stuff to do that is easy to understand, with clear goals, is what makes players want to stay more than a few seconds.

- STORY- Even fun activities get repetitive unless there is a larger meaning and purpose. Having a longer-term purpose or story that players can relate to is what makes them want to keep coming back. Shooting hoops is fun, but doing it everyday for hours can get boring quickly, unless the activity is part of a larger story like training to defeat an old rival team.

- COMMUNITY- All good stories need an ending, but the meaning and purpose that you get from being part of a community can last for years. The games that we keep going back to over and over are the ones that let us connect and be around people that we care about.

All these four elements are important to create a successful game that follows the sequence stand out-connect-engage-grow, but some are more important for one step and some are important for others: standing out depends much more on the art and how things look like than on the details of the story, but engagement depends much more on the mechanics and story than the art, and growing depends heavily on the community building aspect. I’ve seen many good games that don’t succeed because they lacked one or more of these important elements.

It is also important to notice that most games, from free-to-play mobile games to VR experiences and educational games, will benefit from having all these ingredients. If you decide that you don’t need one of these ingredients, if you think don’t need a story or you don’t need community building mechanics, at least you should have a clear reason why not, and you should have an idea of how are you going to get your game to stand out, connect, engage, and grow with the ingredients you choose to include.

There are other elements in a game that are very important like monetization, which is essential to make the game development sustainable. Or marketing, which can help your game get noticed. But the part of marketing that I think is more essential is not the promotion itself, but defining and thinking about your target market, and getting feedback from your target players all through out the development process. Then, your art, mechanics, story and social mechanics will resonate with your players, and your marketing will be embedded into your other elements.

Power Up With a Theme

What I’ve noticed through the years is that games are much more powerful and effective at engaging players when all the elements mentioned above -art, mechanics, story, and social interaction- work together and reinforce each other. Having a strong “theme” will help tie together the elements of your game and will make much easier to connect emotionally with your players. But for a theme to do that, you need to have the right understanding of what a theme is. Theme is not topic. Saying you want to do a pirate game is not enough. There are many different potential approaches to a pirate game: is it about gathering treasure? Is it about fighting the law? Is it about ship battles? It is not about a conflict either. Defining your theme as the conflict between pirates and the Spanish Armada is not enough. You need to pick a side, you need to have an opinion about the topic or conflict you are talking about: ” A pirate life is a wonderful life, because it is more free and exciting.” When you state your theme as a clear point of view you get a much clearer idea of what mechanics and what stories you need. In this case, it all would need to revolve around the excitement of being a pirate and being free of responsibilities and commitments. In his book “The Art of Game Design,” Jesse Schell relates an example from when we worked on a pirate’s virtual reality ride for Walt Disney Imagineering and DisneyQuest. In his book he writes how as soon as we nailed down a theme for the ride, many of the design decisions about art style, game mechanics, story, and even technology became clear. As a result all these ingredients ended up supporting each other to create a much more powerful and award-winning VR experience.

Conclusion

There are 5 ingredients that in combination help your game be much more engaging and successful: art, mechanics, story, community, and theme. When you put those things together in a game or experience: art that resonates with your audience, mechanics that are fun and have clear goals, a story that adds meaning and context, a community makes you feel part of something larger than yourself, and a theme that ties it all together and connects to points of view that you resonate with, you get a much more engaging experience, and your chances of success grow exponentially.

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Added on 3 November 2016

By Felipe Lara

0 Comments

What is a successful game?

Defining game success in terms of profits is the easiest and simplest. If game profits are higher than our investment, the game is successful. However this view does not help us know how to make a successful game: what ingredients to use and what processes to follow. How to be profitable depends on your game’s business model, which can vary widely from a free-to-play casual game to a premium VR experience. Furthermore, in some cases success might not even be about profit, but about teaching something or about creating a change in behavior like in the case of many educational games.

If you are trying to make a successful game it is much more useful to define success in terms of player engagement. In most cases there is a strong correlation between player long-term engagement and profitability. But more importantly, if you understand more clearly how player engagement works, you can map the engagement sequence to the ingredients you need to add to your game and the decisions you need to make during game development.

How Does a Successful Game Look Like In Terms of Player Engagement?

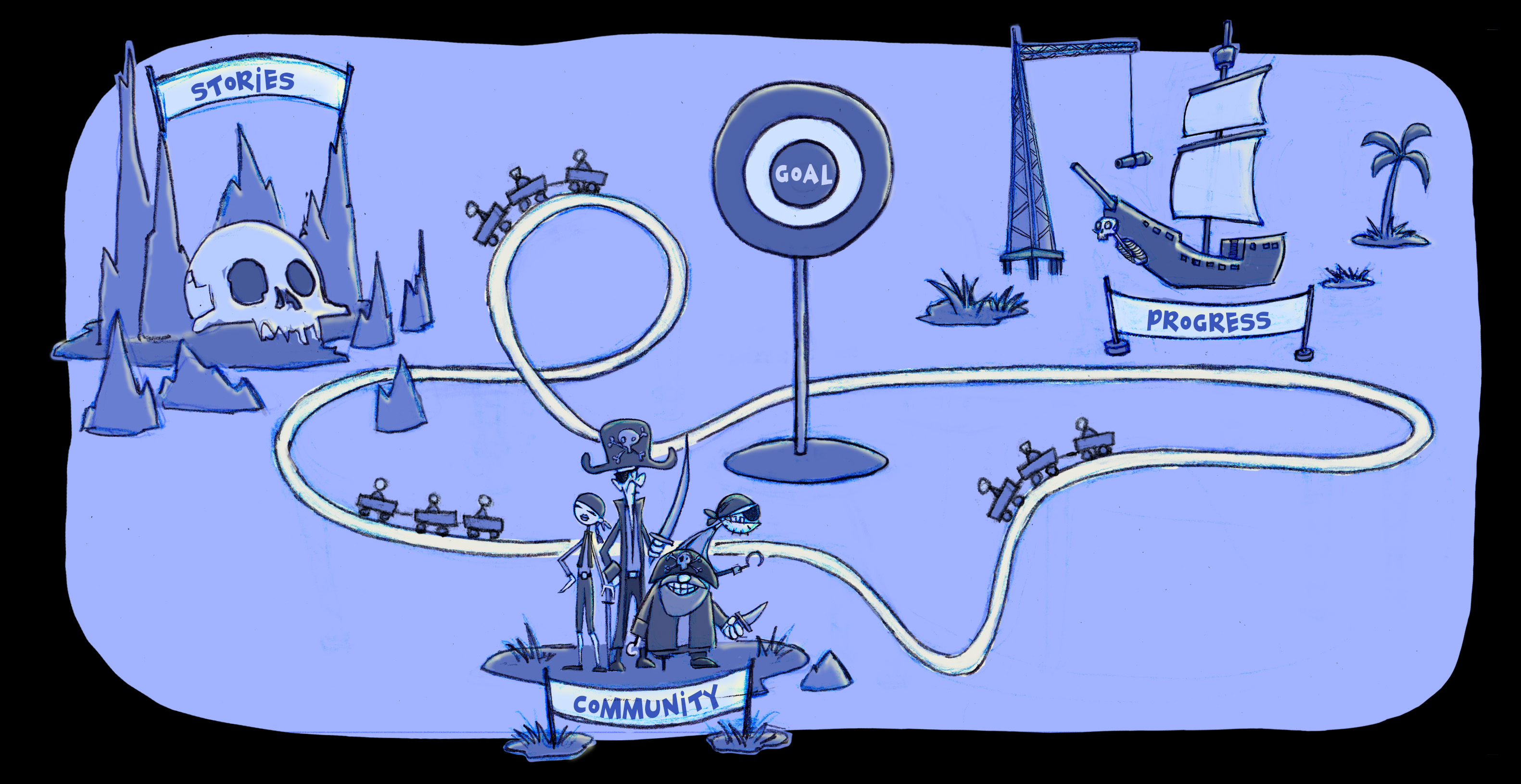

A successful game needs to do 4 things in a sequential order:

- STAND OUT: First the game needs to stand out or be noticed, if nobody is aware of your game nobody will play it. Standing out is about the first impression, it is mostly about looks, no time to explain new game mechanics and stories. The challenge is finding a balance between familiarity and novelty, something the player understands but different enough from all the other apps that crowd the app store to stand out.

- CONNECT: Second, the game needs to connect with players and make them interested in finding out more. Somebody yelling in the middle of the street will get noticed, but the act of yelling itself won’t get people interested, people will only respond if they connect or resonate with what they hear. The same happens with games that get your attention in the app store. Or in the first couple of minutes of free-to-play game.

- ENGAGE: Third, the game needs to engage players and keep them playing for a while. Maybe not the case for all games, but in most cases the longer players stick around, the more profitable the game is. More chances to monetize, more chances to get subscriptions, more chances to get recommended to friends, etc.

- GROW: Finally, the game needs to find a way to scale or grow its player base. The best way to do that is by doing two things: keeping your existing players, and adding features that make them want to invite their friends and promote your game.

Knowing that you need your game to go through the sequence above will help you choose the right ingredients to fulfill each of the steps. For example, one of the best ingredients for standing out in the crowd is having unique art; and one of the best ingredients for growing your game organically is by adding social mechanics that form a community around your game. There are in fact a few key ingredients that can be combined to fulfill the sequence above and create long-term engagement. I will talk more about them in a following post.

But First Clarify the Why and the Who

Your Goals

Of course none of the previous stuff matters if you are not reaching the goals you were trying to achieve with your game in the first place. You might be attracting players and keeping them around, but if you are trying to make an educational game and your game fails to educate, you are not succeeding even if you have tons of players sticking around. The same goes about monetization: if you have hundreds of thousands of players but you are not monetizing or reaching the profit you were looking to make, you are failing. You need to make sure that as your game connects and engages it is also teaching and/or monetizing. That is a big part of the trick, but I’ll save that discussion for a few posts down the road, for now let’s stick to the basics: you need to have a very clear idea of what are your goals and make sure that everything revolves around that.

Your Target Players

Just as important is to have a clear idea of who is your target player. The things that I need to do to stand out and connect to kids are very different from the things I need to do to stand out and connect to young adults. One of the main mistakes I’ve seen in my years developing games is trying to make something that is appealing to everybody, or to a very wide range of people. Trying to please all usually ends with not really pleasing or connecting with anyone.

Conclusion

A good first step towards creating a successful game or a successful VR experience is defining how does it look like in terms of player engagement. Player engagement usually follows a specific path with specific steps: stand out and be noticed by your target audience, connect with them, engage them to continue playing for a while, and finally make them want to share your game with their friends so they stick around and help you grow.

Once you have a clear idea of what the game needs to do, you can look for the right combination of ingredients – art, game mechanics, story, and community building- that can take the players through the engagement sequence. In another article I will talk more about how these ingredients relate to the engagement sequence.

Added on 2 November 2016

By Felipe Lara

0 Comments

We all want to make successful games: innovative, loved by players, and profitable. But if you have been around game development for a while, you know this is hard to do. There are a lot of risks and pitfalls along the way. The goal of this blog is to help you figure out the ingredients and processes that can help you make better and more successful games.