4 Prototypes That Will Help You Survive The Road Towards a Successful Game

Added on 28 February 2017

By WpFlara!-14?!

0 Comments

If you have led a team in the development of a new game, you probably felt at some point like the clown in the illustration above: trying to entertain people, while juggling 10 things at the same time, trying to navigate through a flimsy thin line without falling, and pulling your team along for the ride. The fact is that making games is risky business. There is no way around this, but prototyping the right things will help you reduce risk greatly.

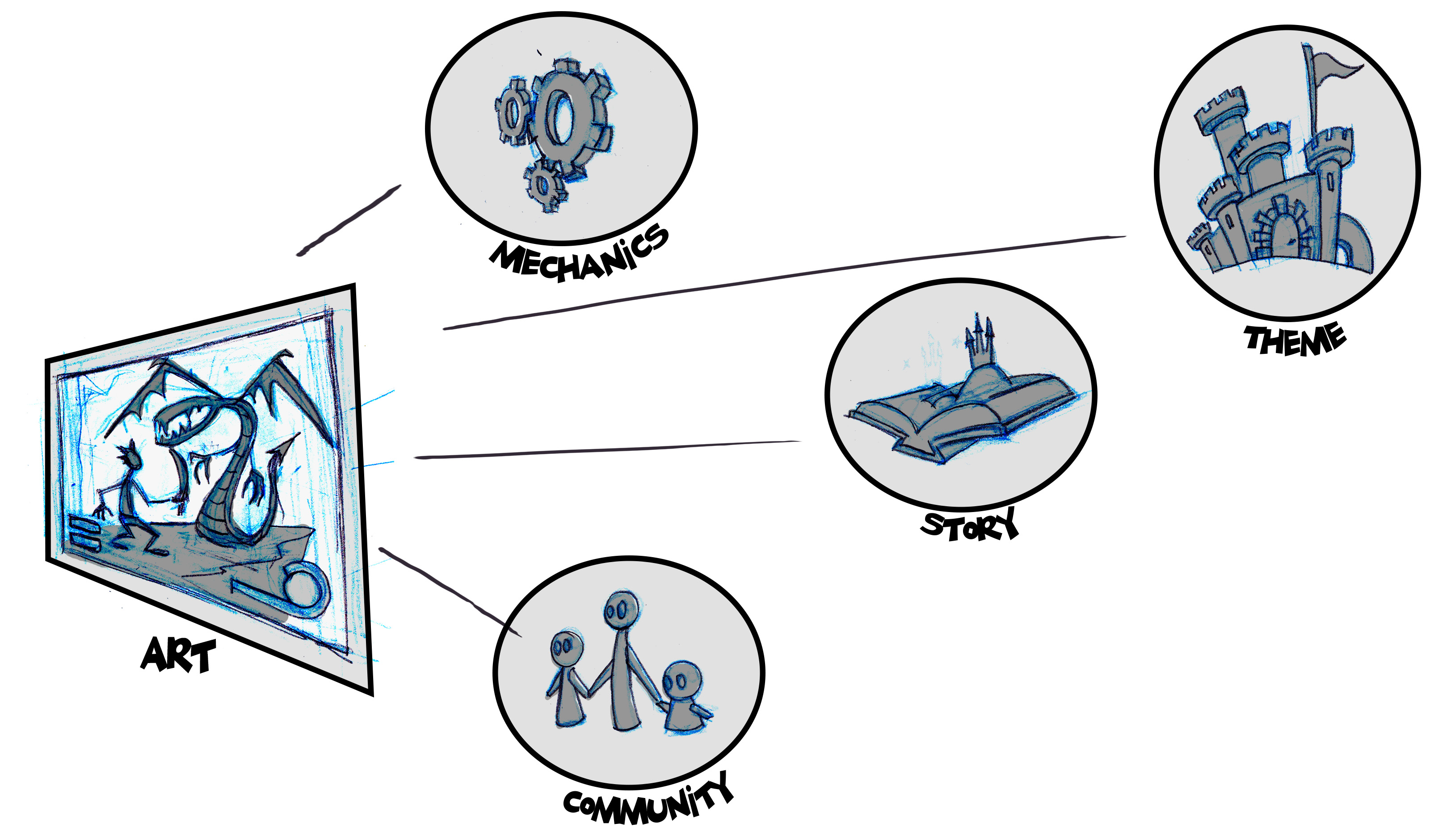

The main risk is of course figuring out what game you should build – what combination of game mechanics, compelling art, storytelling, and social will attract players and keep them engaged long-term. But this major risk is composed of many smaller risks: Do your game mechanics engage players? Does your game run smoothly in the delivering platform? Does your game stand out from the competition? Etc. Although there is no way to getting rid of all risk, you can reduce and keep your risks in check before too many of them pile up and bury your game down.

This process of figuring out what product we should build is what is called product discovery. In the last few years, new methodologies have emerged that have changed the way we look at this process: lean start-up, design thinking, rapid prototyping, user-centered development- all involve prototyping and user-testing as essential tools to help us learn sooner rather than later what is the right product to build, connect with our users, and reach our goals. For a big picture view of product discovery I recommend this presentation by Teresa Torres, a coach and consultant who helps companies figure out how to build the right products.

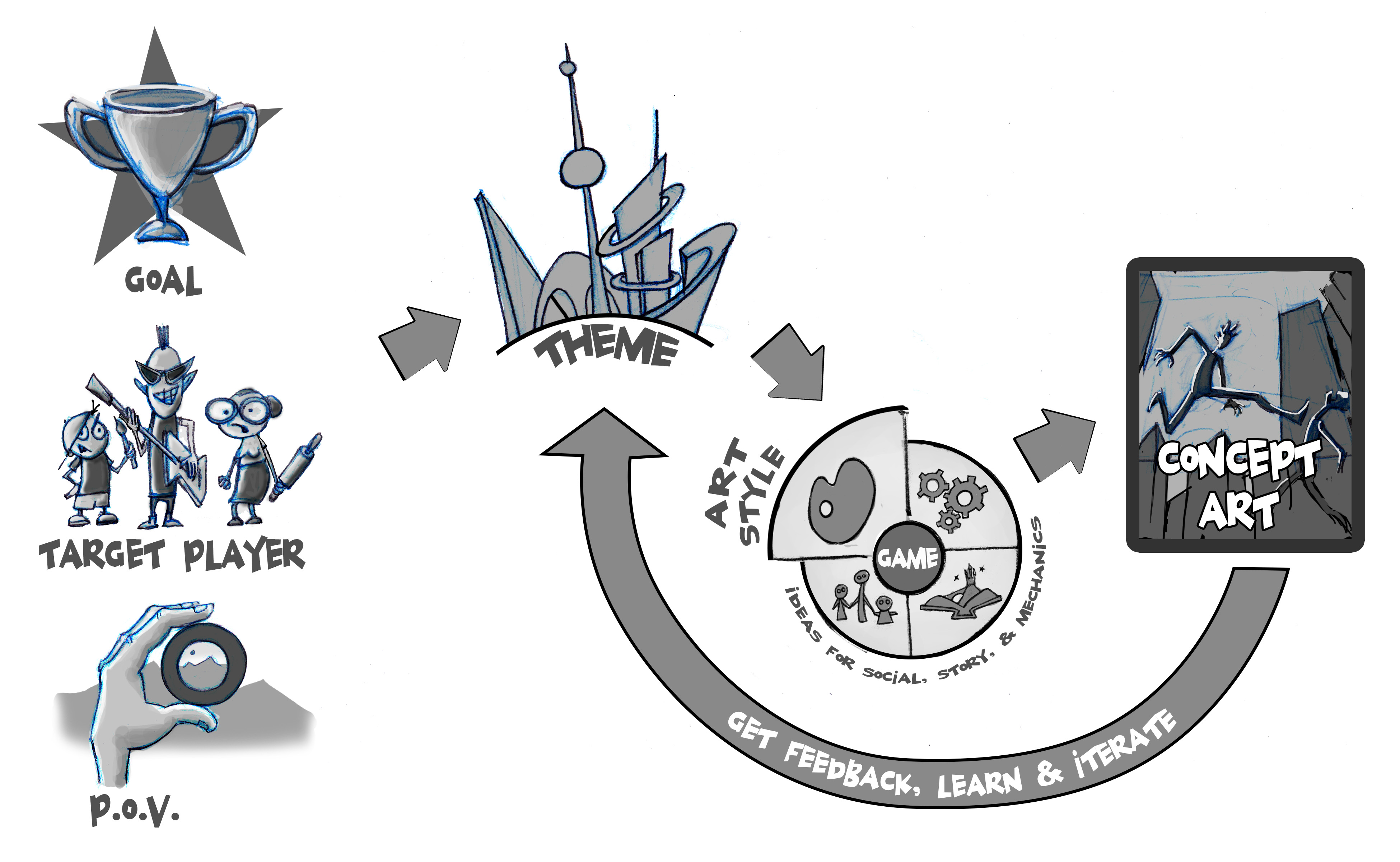

In this article however I want to focus on 4 prototypes that will help you create a game with long-term engagement and growth. I talked in previous articles how successful games and experiences need to go through four steps: first stand out so your target players notice you, then connect with them at an emotional level so they are willing to give you a few minutes of attention, then engage them so you can keep them for longer time, and finally get them to help you grow by sticking around and inviting their friends to join. Each of these steps has at least one major risk:

- Is your game going to stand out in the crowd?

- Will players who see your game care about trying it out?

- Will your mechanics keep them engaged?

- Will they talk about your game with their friends and recommend it?

The 4 prototypes bellow will help you validate potential solutions to overcome each of these steps:

1. Concept Art.

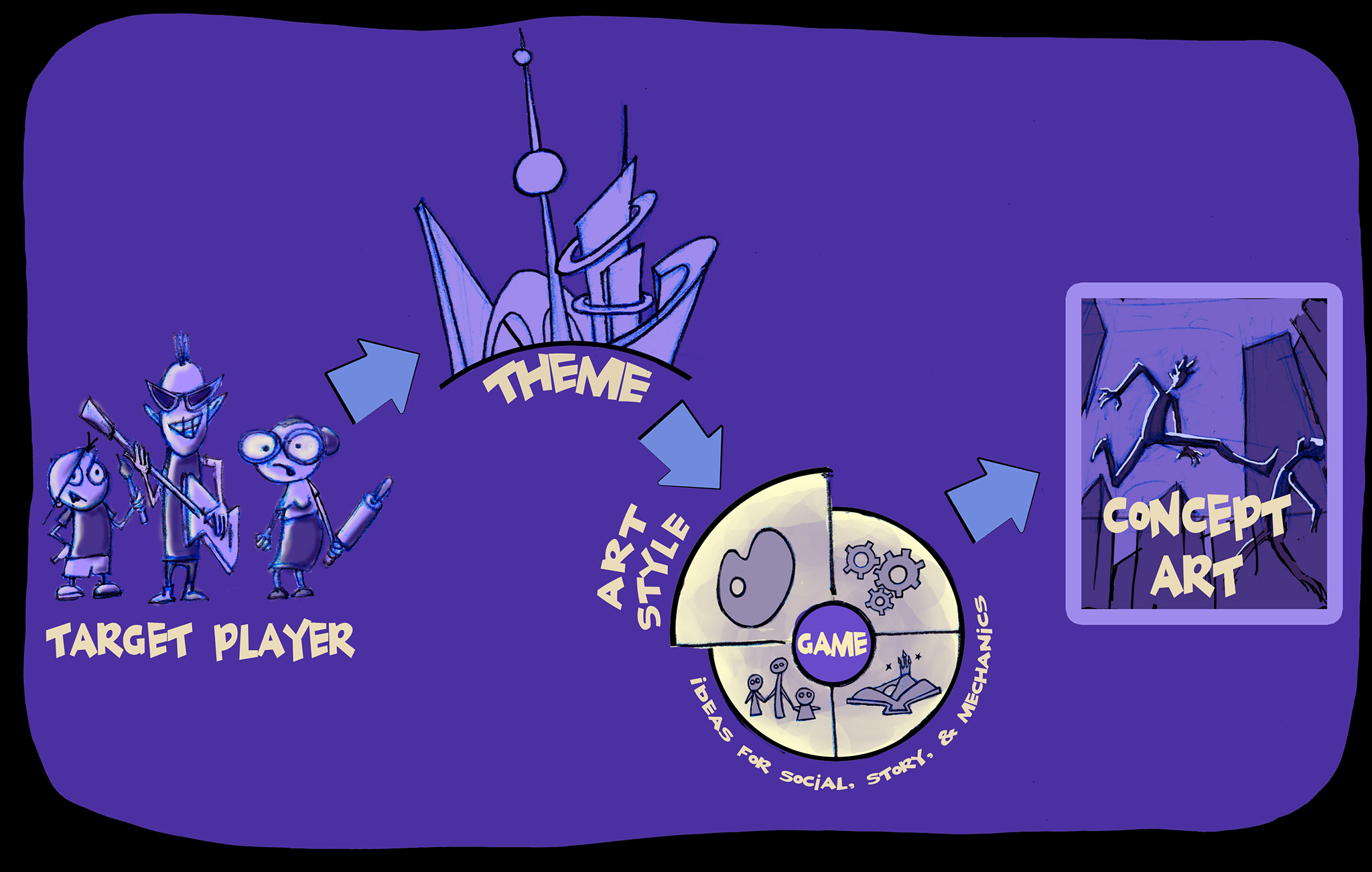

It might sound strange to list concept art as a prototype, but the right concept art can be a very useful tool to test two of the foundations of a successful game: how to stand out and how to connect emotionally with your target players. In reality players do not connect to games and experiences exactly because of the art itself, but rather because of the attitudes and points of view that the art reflects and that resonate with them -what I have called Theme in previous articles. Art alone will not sustain players’ interest either; the “cool look” factor wears off quickly and needs to be accompanied by game mechanics and stories that continue reinforcing the Theme that got players’ attention in the first place. However, art is the easiest way to explore and start testing which Themes resonate with your target players and which ones don’t. Finding the right Theme and the right representation of it, will take you a long way towards standing out and connecting quickly with your players.

2. Core loop.

Having a core loop that does not engage players is probably your highest risk and one of the most common causes of failure. All games have a core set of activities that the player repeats over and over to advance through the game. These repeatable activities are usually called loops and are the engine that keeps the player’s interest going. If this core loop does not help the players keep their interest and fulfill at least some of their initial expectations, they will quit and your game will be like a leaky bucket that needs to be refilled with new players constantly. Needless to say, it is much harder to reach any success with a leaky bucket. I have seen many developers trying to add more and more features to their games, hoping that these features will cover the hole in their leaky core-loop. The problem is that more features rarely solve the problem, and fixing the core-loop is much more complicated and expensive once it is interconnected to a bunch of secondary features. In the end, they would have been better off if they had taken care of their core loop before adding a bunch of extra features and smoking mirrors. Prototype your core-loop and make sure it works before trying to add more features!

3. On-boarding experience.

Once you have an engaging core loop, you need to make sure that players get to it. This means that the onboarding experience -the time since your players first start playing your game until the time they get to the core loop- needs to be as smooth and engaging as possible. Having an engaging core loop won’t help if players quit the game before getting to it. Prototype and test your onboarding experience.

4. Social loop.

There is a sequence of social activities that happen around games that go viral or form a strong player community: players are compelled to share the game or the results of the game with their friends, which in turn are compelled to start playing the game and tell other friends about it. These activities are sometimes structured as part of the game mechanics inside the game, like in Clash Royale where the core mechanics of the game involve playing with other players, joining clans, etc. But social loops can also happen outside of the game itself. In games like Minecraft or Little Big Planet players create their own content and share it in forums and social networks, and although these activities happen outside of the game, they effectively promote the game to others. Social loops outside of the game are harder to measure, but even looking at number of social media posts and likes can veer you in the right direction. If you care about having a game that can grow its user base organically without a highly expensive marketing campaign, you need to prototype and test your social loops.

Conclusion

Risk is part of the thrill of making new games and experiences, but building the right prototypes at the right time can help you keep your risks in check before they get out of hand and you fall into the sharks. The 4 prototypes above are important because they help you test and validate how your game will engage players, but they are not the only ones. In the end prototyping is about mitigating risks and the general rule is that you need to build the prototypes that tackle your higher risks first; this could be more related to the technology, or to your business model, depending on what you are innovating on.

What prototypes do you consider the most important ones? Let me know in the comments.